field notes

tajikistan and kyrgyzstan, 2013

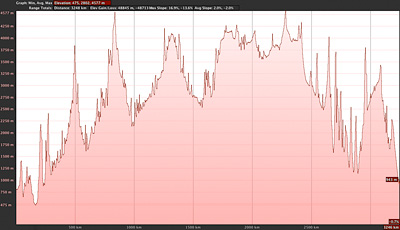

After decades this was the first time that I participated in a purely scientific expedition. It was also the longest and largest photography trip that I ever had in my life. It took 43 days for 14 people divided in 3 groups to travel through 3 countries of Central Asia, over more than 3000 km. We went through high mountains of Pamir and Alai at altitudes of up to 4500 MASL, collecting animals and plants in some of the least researched areas of Central Asia. My task was to create quality images of wildlife and landscapes for use in scientific papers, books and magazine articles.

This trip was for me in many aspects a completely new experience. I usually prefer to travel independently and organise everything myself, but this time another person was in charge of organisation and planning. I had tried to make my route, duration of stays at each place and daily activities compatible with the work plan and interests of other group members, although my work was regarded by the expedition organisers as a priority. Normally I travel either alone or with my wife, and this was the first time when I traveled with people whom I didn't know before. However, I am glad to have had an opportunity to meet new people who were great travel companions and became my good friends. The budget of the expedition was very tight, therefore also critical things that I normally wouldn't save on, such as transportation and communication means, were subject of severe cost cuts. In many situations this restricted our movement, influenced the organisation and the work of all of us. Surviving in the mountains without cooking fuel and enough food was also a challenge that I never had before. I also never had been before in so tough environment and at so high altitude for so long. After health difficulties during my trip in the Ethiopian mountains (see Field Notes: Ethiopia, 2012), I had prepared myself for Pamir with extensive physical training, with very positive results: Even very intensive and long physical activities at altitudes of 3500 m and higher were no problem this time.

When reading this report, please bear in mind that it is written strictly from photographer's viewpoint, and forgive me if my judgments would be not correct or not applicable for other kinds of travellers. This is why also my co-travellers who were with me in this expedition and who may read this text should excuse me if some of my thoughts and conclusions would appear biased or not entirely positive. My analysis is strictly by a photographer for photographers.

the route

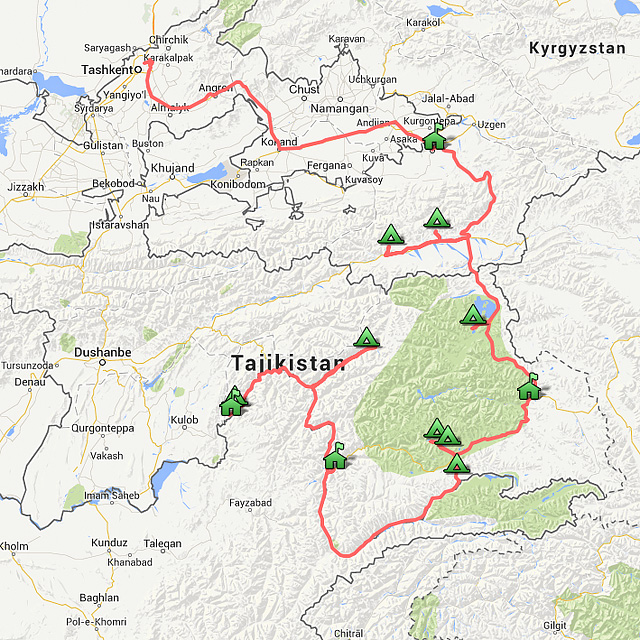

The time for travel and the route had been chosen mainly according to the needs of the researchers. I was more or less free to define my places of interest and could insist in staying for a couple of days in each of them, but not all my wishes were compatible with the goals of the others. Therefore, as always in such cases, different priorities had to be agreed, and the itinerary of my group was as of the whole expedition was a result of compromises. Also logistics issues and local situation in some areas led to changes in the plans, hence the final route deferred from the initially planned.

Our expedition travelled in 3 groups. Each of them had different members at different parts of the way. Two groups of zoologists explored the Pamir area of Tajikistan and went together to Kyrgyzstan where they met the third group consisting of botanists. Additionally, I spent a week in western area of Pamir mountains before the other expedition members arrived. Therefore I arrived in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, earlier than the others.

My trip began in Dushanbe where I met the organiser of my stay and work in a private game reserve near Dashtidjum — a protected area in the mountains near Tajik-Afghan border. He brought me from the airport directly to that place. After a week of work there and having enjoyed the incredible hospitality of these people, I continued my way by car together with another colleague to the valley of the Vanj (or Vanch) River in Western Pamir. The rest of the expedition members found us there. We all spent the next 3 days together. Two of us stayed for 2 days more in Vanj Valley, and met the others who left earlier in Khorog — the main town of Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region (a.k.a. GBAO). In Khorog we split us into two groups. Each of the groups got one of the hired cars and took its planned route through Pamir. The two routes were similar. The main difference was in the length of stays and the time on the move. My group was supposed to make longer stops at pre-defined places of interest and to pass the distance between them quicker. This didn't always work well with the first setup of the group on the way to Murghab but overall this plan was fulfilled. In the first 10 days of the expedition we visited mainly high montane desert and lakes in Central Pamir. The longest stay was at Yashilkul Lake. From there we went to Murghab, the biggest town in the Eastern Pamir, and met the other group there. In Murghab the groups exchanged some of the members. After a short stay my group went directly to the south eastern bank of Karakul Lake. At Karakul we worked for 5 days, till the second group joined us. After that we travelled together to a remote place in Alai Valley in Kyrgyzstan in the area of Daroot Kurgon town where we spent a week. Then the botanists group arrived from Uzbekistan and most member of the previous two groups went to Osh (the regional capital city) to go home from there. One of the zoologists and I continued the trip with the botanists and came to Osh a week later. From Osh a car brought me and two other members of the expedition to Tashkent. From there we took a plane back to Europe.

Below you see my route on a map. To view it in Google Maps, click on the picture.

The actual itineraries of all groups were different than initially planned. For instance, in the Pamir we had to skip the Afghan part of the route: Initially a trip to the Wakhan Corridor in the Northern Afghanistan was planned, but shortly before expedition start we recognised that we had neither time nor enough money for it. Also the route in the second half of the trip — through Alai in Kyrgyzstan — had to be much shorter than initially planned due to absence of cars as a result of financial problems.

The whole expedition had to return via Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan because it wasn't possible to go back from Alai Valley to Dushanbe. Some of us flew back home from Bishkek, and the majority of expedition members went by car to Tashkent to take a flight from there. The roads going south, from Kyrgyzstan through the high Pamir, were closed for foreigners due to a continuing conflict state between these two countries. This circumstance and the lack of sufficient financing of such a long expedition were the reasons why I was viewing it as a mistake combining an already long trip through Pamir with almost as long one through Alai. Splitting it in two expeditions would have been a better idea.

Even 6 weeks that we had were too little time for such a huge itinerary. On Pamir roads a car can typically go not more than 150 km per day, and even 3 days at each location were not enough in this region for achieving good results. Since the time was overall too short, we had to skip many interesting locations or to make only very brief stops — for just 1 night.

transportation

getting there and back home

There were no direct flights to Tajikistan from German and other Central European airports, but many options of transit trough airports in other countries existed. Russian companies and Turkish Airlines had the cheapest offers which, however, turned out to be cost traps for me and others travelling with heavy luggage. I had about 70 kg of luggage, and overall paid over 2000 € for it on the flights during this trip! Unfortunately a half of this amount was my private money. For a similar amount, I could take two seats in economy class or a business class ticket in planes of other companies and have not only more comfort but also all my baggage included. However, it was decided to go for the “cheapest” ticket offers we could find. At the end the combined cost of the tickets from Munich to Dushanbe and back from Tashkent was only one fifth of the real total cost of the flights. Even with those 900 euros that I paid privately I could have booked a much better roundtrip flight with much more baggage included.

Air Baltic, the Latvian airlines, was the “cheapest” that flew to and from Tashkent, but I would recommend it only to people who have only carry-in luggage or very little check-in luggage. When you are going to spend 6 weeks in extreme outdoor conditions and even if you aren't a photographer, you would most probably take quite much camping equipment, cloths and other stuff. Then this company isn't for you because it takes your baggage at extra charge. On return flight, I had to pay them over 1000 euros for my check-in baggage. To Dushanbe I flew by Russian airlines. Although I had purchased it as a ticket for one single trip, that were three separate flights — Munich-Moscow, Moscow-Yekaterinburg, Yekaterinburg-Dushanbe. I learned it when I was checking-in in Munich — too late to correct this mistake. A check-in of the baggage wasn't possible for the whole trip but only for each of these three flights separately. At each airport I had to pay more and more for the baggage. The total amount I paid was more than 4 times the ticket price.

With this bad experience I would now recommend everyone who is going to travel from Europe to Central Asia with heavy luggage to consider the offers of “serious” companies such as KLM, Lufthansa or British Airways. Their tickets may be more expensive than of cheap flyers but include more check-in baggage. Another option may be buying two tickets in an inexpensive flight with at least 20 kg included in each, or a business class ticket with more check-in baggage. Of course, if it were my private trip, I would try to reduce the baggage as much as possible thus leaving some of the items at home that I took this time with me. Normally I travel with 40 kg of luggage at the most. They fit into the weight included with a KLM ticket, for instance.

on and off road

Of course, as usually in such countries, in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan there was no car rental for self-driving. Hiring a driver with a car wasn't a problem in general. However, it wasn't easy to find an experienced overland driver with a good car — particularly considering the imperative of keeping expenses as low as possible.

Compared to many other regions with similarly poor infrastructure the prices for driver services in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan were quite low. 100 US dollars per day was the highest price I heard. The lowest prices that could be achieved through negotiation were around 60-70$ per day. An even more low-budget option was to negotiate payments per kilometer instead of per day. In such cases the drivers requested at least 0.75$ and additionally some daily money — something like 10$ per day. This was not a bargain when the distances of daily drive were large. Then the resulting price could be even higher than if it were a fixed per day amount. However, it was cheaper on those days when the car wasn't moving. Then the driver was only receiving his 10$.

One of our drivers exchanging a wheel after a tyre got punctured. On some days he did it up to three times. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

I was surprised that this expedition was expecting that the driver would also cook. In such countries men normally don't do this, and in a traditional family cooking is a function of a woman. I had expected a specially hired cook to be in each group, but there was none — again because of the urge to save money. The cars were either Toyota Landcruiser or Mitsubishi Pajero, i.e. with maximum 4 passenger seats that were occupied by expedition members. Even if they had decided to hire one cook for each group, there was no seat for him or her anyway. When you negotiate the prices and services of the driver, he would probably agree also to cook, but be prepared that afterwards he wouldn't even be able to make fire. Also he may turn out just to be lazy — like one of our drivers in Pamir who didn't want to help with collecting firewood or doing the dishes, not to mention cooking.

Fuel was not cheap in these countries but a little cheaper than in Europe. The usual price for petrol in cities and towns was around 1€ per litre. However, in remote places petrol stations were completely absent, and local people were often trying to make more money re-selling fuel at higher prices of up to 1.2€ per litre.

The cross-terrain capabilities of GAZ 66 are really impressive but this car is absolutely terrible for drive at long distances: The fuel consumption is huge. The driver of this vehicle requested from us 35 US$ for fuel for a 15 km roundtrip between Poimazor village and Bear's Glacier in Vanj Valley! The car was in so bad technical state that it was stopping every 500 meters, and we had to walk while the driver was fixing it. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

In high altitudes the fuel consumption increases due to low level of oxygen in the air. Even car models that are otherwise considered as economical consume much more fuel there also due to other factors such as poor driver skills, bad technical condition of the engine, too frequent driving with low speed. I was surprised that a not very old Toyota Landcruiser that we hired for a part of the route from Khorog to Murghab needed up to 25l of petrol per 100km. Beware of old Soviet cars, such as GAZ 66. They are petrol powered and will need really much fuel for driving in the mountains. Diesel powered cars may be available but for unknown reason were rare this time.

Travellers should be advised to calculate the quantity of fuel needed for the trip between the places with petrol stations and to take fuel accordingly in spare canisters, or, if uncertain, just to take as much as possible — at least 3 canisters per car. In this expedition it wasn't done, and we paid a lot for fuel that we were buying in villages. Since fuel reserve, food and other supplies need quite a lot of space, cars should be hired not one per 4 or 5 passengers as in this expedition, but per 2 or maximum per 3 (plus driver). Then there will be enough space for luggage, reserves and spare parts. Unfortunately, because we were too many in a car we had even difficulties to accommodate our luggage and belongings.

by foot

Walking in the high Pamir and Alai can be very challenging because of altitude and rocky terrain, and of frequent need to climb steep slopes. When you are anywhere in this region, you are already at an altitude of at least 2500-3000 m above sea level. Therefore altitudes of 4000 m and higher can be reached very quickly in one day's walk by anyone in shape. Walking all the day will be much more difficult for a photographer carrying his heavy equipment in the field. Therefore you have either to carefully select your equipment and take only the most important items with you or to have a helper who would carry at least a part of the load. Unlike in most tropical areas of the world, in Pamir and Alai human porters aren't common. Even if you'd hire a person to help you, he will come with a donkey, a horse, or even a camel. Prices are always subject of hard negotiation. Hiring a camel would cost you from 15$ a day. A horse or a donkey would be much cheaper. If you know how to handle a donkey or a horse, you can try to rent one. Also rental of riding horses should be possible but I can't report any further details about it from personal experience.

Very sturdy and comfortable shoes are absolutely a must. In most places good trekking boots should be fine, but mountaineering boots are the best choice, though not a requirement. Of course, it is absolutely wise to have a spare pair of boots because the terrain is extremely tough, and your shoes are in constant danger of getting damaged beyond repair.

Not only for photographers carrying a big load in the mountains but for anyone also having a pair of trekking poles should be strongly recommended. It is very important to have a good quality poles, such as LEKI, because they will be subjected to very harsh treatment when you will be ascending or descending stony slopes and debris.

logistics

Providing everything necessary for the work of a large expedition is a very difficult job, particularly when financing is extremely limited. To find reliable local helpers is difficult while you are in Europe. Travellers who don't want to do it themselves can address one of Tajik or international tourist companies that work in this region. However, there is objectively no such need because everything can be arranged and purchased upon arrival, but you have to plan several days for preparation of the trip. In the concrete case of this expedition, the person in charge of organisation just arrived in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan and the starting point of the expedition, several days before arrival of the rest of the participants. He arranged cars and purchased most supplies. As usually in such countries providing logistics was not without peculiarities and problems.

communication

After transportation, communication is the most important part of logistics if a trip goes to a country or region with poor infrastructure. Everywhere where people live you can find food, water or place to sleep, but without telephone or Internet line you'll be cut off from the rest of the world, thus from your business contacts, friends and family. This is not only an inconvenience that disturbs your business and social ties: Lack of communication means may be fatal in case of danger, illness, accident or other emergency.

Inadequate means of communication are usually one of the main reasons of coordination problems when several groups of people travelling separately from each other but still have to follow a certain common plan or schedule. This was the case in this expedition, too: Communication between three groups was absent most of the time because the organisers had decided to save money on it. As a result, it was impossible to discuss and agree on operative changes of the route or of the schedule.

Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have a fairly extended cellular phone network. The Russian companies Megafon and Babylon had the best coverage, however, with substantial regional differences: While Babylon was better available in Western and Central Pamir, the reception of Megafon was better in the east. Other smaller cellular phone providers were offering the cheapest tariffs but their networks were restricted to the capital and large towns. In Kyrgyzstan, another Russian company, Beeline, appeared to have an extended and reliable network. O2 — my mobile phone provider in Germany had roaming with all networks mentioned here.

When looking for a pre-paid offer and choosing a provider don't rely on recommendations of locals and, of course, don't ask the distributors of SIM cards. People who live in the cities most likely won't know in detail the situation along your route in the remote parts of the country. Dealers of mobile operators may be interested just to sell a certain product, hence asking them for an advice may be also useless. Instead search in the Internet the sites of GSM operators who work in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan and compare the information about their network coverage. Never look just for the cheapest offer because it may prove to be useless later when you are off in the field.

The best communication means throughout the territory of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, like in other similar countries, is a satellite phone. During the preparation of the expedition I was suggesting to have at least one satellite phone in each group travelling separately. Unfortunately, a mixed way was chosen: I brought my Thuraya satellite phone that I had prepaid with 150 units and was using it in my group; the other groups were using cellular phones wherever possible. In reality, the communication between groups almost never worked because they had bought the SIM cards of the cheapest provider who had almost nowhere reception in the places where we were traveling. I also suppose that this provider had a non-woking gateway to Thuraya network, so that I wasn't receiving text messages that people were sending me from their mobile phones while I could send an SMS from my Thuraya to any of them. I could also call any cellular phone, but wasn't receiving on the Thuraya any calls from the cellular phones of people in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

I wouldn't recommend therefore to rely on GSM network to anyone travelling Pamir and Alai who want's to stay in touch with others and with people at home. First, the cellular mobile network doesn't cover the complete area of the mountains, and large gaps in reception have to be expected. Second, calling your home may be more expensive than with a satellite phone or even impossible if you have a mobile tariff that excludes calls abroad. I also observed that even calls from Tajikistan to Kyrgyzstan on an Uzbek mobile phone were failing. In this expedition, my main communication means was a Thuraya satellite phone that I was using not only for texting and calling people at home, but also for sending messages to Twitter that were automatically being posted to my Facebook page and the WordPress blog. Of course, I was also receiving calls.

Most hotels offer Internet line over wi-fi free of charge. It was in the hotel where a stayed in Osh so, and I could use Skype for calls and write mails from my laptop and iPhone.

accommodation

A yurt is a typical house of seminomadic pastoralists in Kyrgyzstan. These people are extremely friendly, and a traveller will be usually welcome to stay in their yurt. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

Obviously, as a photographer you need to stay in a tent to be close to your subjects. Otherwise, there are very many opportunities for inexpensive lodging, including meals, in so-called “home stays” — families of local people. Along with the need to be as close to the location as possible, I didn't like to sleep in someone's home in a room together with others. I found it better to have a private space that I didn't share with anyone — which was my own tent. It seemed to me, however, that other participants of the expedition were rather inclined to go to a home stay or to a hotel wherever possible. I was insisting on sleeping in the field and we did it, but I felt that not all in my group were happy with it.

In many places, it wasn't possible at all to find other accommodation than own tent. Therefore, if you are going to photograph nature in Pamir or Alai you have to bring a tent with you even if you'd seek an opportunity to stay in the homes of locals.

My tent and the landscape in Little Alai covered with snow in a morning in August. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

Your tent has to have qualities that are essential in this region: It has to be very strong and require only a few minutes to be pitched. Of course, it should be a double-shell tent, preferably with the ability of the outer shell to be pitched first. At high altitudes in Pamir and Alai the wind was blowing permanently. However, I don't know if it is in every season like this or only in July and August. Anyway during this trip even periods with weak wind were rare. Usually, the wind was strong — sometimes even so that I could barely stand on my feet. Also the soil was very stony and hard so that it was often almost impossible to fixate the tent firmly enough. This was a situation when the advantages of a good and therefore expensive tent were obvious.

My cheap tent was getting almost flat when the usual strong wind was blowing. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

The choice of inexpensive tents is very broad. Such tents also look very nice and similar to some very expensive. Therefore, many people are tempted to purchase one, and so was I. As I reported in my Field Notes from Ethiopia, 2012, I had such a cheap tent on my Ethiopia trip that I gave as a tip to my guide before departure back to Europe. This tent wasn't good but survived the weather and climate of Ethiopian mountains. Since I had been planning to go to Ethiopia again this year, I purchased another such tent in order to use it during the trip and to leave it in the country after that. I had to delay my plans for Ethiopia to the next year because I was invited to participate in this expedition to Central Asia. Since I already had that tent, I took it also on this trip expecting to be able to use it just like in Ethiopia because I thought that the climate should be similar at the same altitude in Pamir and Alai. I understood that this assumption had been wrong already on the first days and nights at an altitude over 3500 MASL. In Central Asian mountains everything is much tougher than in Ethiopia — the climate, the relief, the soil. Although a cheap tent may withstand it most of the time, but it is really no fun to pitch it and try to sleep in it in the wind, under ice cold rain or snow. It may even become dangerous, when half an hour remains till it gets completely dark, but you are still having a fight with your already completely wet tent that doesn't want to stand under heavy rain and wind. Everything can become even worse if it starts snowing. The snow will be wet and heavy, and you will need to knock or sweep it from the roof of the tent now and then in the night instead of sleeping because the tent may collapse under this weight.

Therefore I will do it myself the next time and am recommending everyone going to high mountains to have the strongest tent you can afford, and to try to afford the best and strongest one. Anyway, your tent has to satisfy the following requirements: 1) to be able to withstand a wind speed of at least 25 m/sec; 2) it should be possible to pitch the outer wall before the inner very quickly; 3) the earth nails have to be very strong and suitable for putting in stony soil. I am sure you won't find a cheap tent with such qualities.

supplies

In both, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, agricultural products are readily available, particularly in the summer. However, their production is concentrated to the areas with large plains, and they are sold either in regions where they are produced or in cities and large towns. Vegetables and fruits may be impossible or very difficult to obtain in mountain villages.

Although Islam is moderate in these countries, so that many people drink alcohol, eat at daylight during Ramadan, etc., traditions may influence the availability of certain food. Obviously, pork is offered nowhere. I don't know if Tajik and Kyrgyz ate it in the times of the USSR, but would assume that the didn't although most of people in the cities were officially atheists. Now, people in these countries observe Muslim holidays, such as Ramadan. Muslims should be fasting during Ramadan from dawn till sunset. However, many in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan don't, so food is being offered in restaurants and on the market during the day, too. Nevertheless, there may be shortage of it or at least of certain products. For instance, cattle isn't being killed during Ramadan but kept for the celebration of its end. Therefore we didn't see meat for sale anywhere during this trip — because we were travelling during Ramadan.

Although it wasn't a really big problem, but I consider it as another planing mistake to choose the time for the trip almost entirely in the period of Ramadan. I can't be certain because I wasn't in this region in other times yet, but it appeared to me that we were experiencing problems with food supplies at least to some extent due to the religious holidays. Anyway I heard people telling that the offer on the market and in shops is better in other time of the year. Therefore, if I would plan myself a trip to this region or to other Muslim country again, I would ensure that it won't be during Ramadan.

Overall, food — both, served in restaurants and home stays and sold on markets and in shops — is very cheap. An exception are imported products, such as fish and meat preserves, that can be more expensive than in Europe. Cheese is totally absent so that I doubt that people there know about its existence — otherwise they would be making it, too. However, sour milk products are being made in all pastoralists' families and can be purchased even in remote places or even obtained free of charge. Home made yoghurt in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan is very tasty and safe to consume. Also condensed milk (in small cans, imported from Ukraine) proved to be good for breakfast and supper in the field. It was sold in most shops. In the same shops we were also purchasing biscuits, noodles, rice, sugar, tea. Coffee is more difficult to find in village shops, but is available in cities. Most of the time in the field we were drinking black or green tea. Sometimes we drank coffee that some of us had brought from home.

On the markets (bazars) you can buy onions, carrots, potatoes, cabbage, melones, watermelons, and plenty of fruits, such as grapes, plums, peaches, figs, apricots, etc. Also dried fruits and nuts are being sold everywhere. They are particularly well suitable for making large reserves for the time in the field.

As I mentioned already in my other reports, people loose body weight in the mountains particularly quickly. There are two factors that influence this: hard physical activity and quicker but less efficient metabolism due to the influence of high altitude. Although many people may be happy with it in their city life, in the mountains there is a danger that you loose too much weight and energy. To prevent it, you need to eat much more than at home — particularly food that is rich with carbohydrates. In our expedition we had periods of food shortage when it had to be strictly rationed. Since I continued carrying my heavy equipment and climbing mountains, I lost around 10kg within a short period of time, and finally was feeling weak. Fortunately, I had brought some “energy bars” — those small food packets sold in sports shops with sweet content that is rich of carbohydrates, proteins, magnesium. I ate them now and then when I was in the field, and, as it already was in Ethiopia, I had a feeling that they were saving my life.

Getting water for drinking and cooking was not a problem at all: It could be taken directly from streams in the mountains. Streams that are looking snow white from a distance come from melting snow or form glacier. They are absolutely clean and their water tastes very good. Other streams may contain some sediment when it rains in the mountains and clay is washed out. The water from them can still be consumed but is not so pleasant. Water could be drunk without any treatment. However, some members of our group didn't dare it and drank the water only after cooking. I had the Katadyne filter that I normally use in Africa but didn't use it this time. Cooking drinking water consumes additionally much fuel and doesn't make any sense.

For making a cooking fire, normally there is no alternative to gaz. Wood is almost nowhere available in these mountains. With a suitable cooker petrol from the car also be used but it should be an exception for emergency cases. Cooking gaz cartridges, as used by outdoor travellers, aren't available in the countries and you can't bring them from home because the airport security prohibits it. There is a better alternative in form of propane tanks that you can purchase in Dushanbe. 25 l tanks are available, and according to my observations, 5 persons need one such tank per 10 days. Since propane tanks can't be purchased anywhere else in the country except in the capital, you have to make a reserve of them for the entire duration of the trip. If you travel alone only with a driver, one may be enough even for a couple of weeks.

If you happen to run out of cooking fuel — like we did — and you have not petrol cooker or no car, you can use dry cattle dung for making fire. It can be found almost everywhere in the mountains. In the areas near settlements people collect it for the same purpose, so large pieces may be difficult to find, but usually dung of cows, horses, donkeys, goats, sheep and yaks is abundant. It is difficult to set dung in fire and it burns bad without wind. Fortunately, wind frequently blows in most places. Anyway making and maintaining fire with dry dung takes very much time, and shouldn't be planned as serious alternative to gaz and petrol.

other logistic issues

Electricity: It is absent almost everywhere outside towns. If you use only cameras for photography and don't spend too many days in the field, you may just get around with a few spare batteries. Otherwise, a power source for charging the batteries is needed. The simplest solution is probably to charge from a car. However, it is possible only if the car is continuously available, and if it frequently moves. I have seen how quickly the equipment of the expedition members who were doing it this way became unusable once the car had left. Even when the car is there, but only standing for several days, its battery may get drained. To avoid this the driver has to run the engine now and then, thus consuming the valuable fuel.

The best way to charge the equipment batteries, particularly in such sunny areas, is to use a solar panel. In the Field Notes from Ethiopia, 2012 I described my Sunload solar charging devices. During this trip I used it, too.

Hygiene: As always outdoors, body care is not easy. Since making fire was difficult and fuel needed to be saved, we did not heat water for washing cloths and ourselves. Cold water had to be used for everything. Although we were usually staying near a lake, it wasn't possible to swim in it because the water was too cold. The maximum what could be done for personal hygiene under such circumstances was washing the hands and the face and brushing the teeth. Opportunities for taking a shower were only in hotels in Khorog, Murghab and Osh.

Currency: Both, dollars and euros (and possibly some other western currencies), can be exchanged in the capital or in large towns, or used directly for payments. Getting local currency outside the capital may be not easy if you don't have enough cash and want to use a card. Debit cards of western banks weren't accepted. Among credit cards Visa was most often accepted, and should be preferred, particularly if you are going to take money from ATM. In the offices of some banks I could use also a Mastercard. Except some good hotels in cities, there were not places where one could pay with a credit card. Payments could be done always in cash — either in national currency or in dollars and euros. Among foreign currencies, dollars were preferred. All payments of big amounts, such as for cars, were done either in dollars or in euros. Travellers to remote areas of the country should be advised to have a pile of dollar banknotes with smaller denomination — 1-20$ — to use them for payment in situation when the amount exchanged in national currency is spent but there is no other exchange opportunity.

Language: In cities and large towns Russian was still spoken and understood by the majority of people. Also increasing number of people were there learning English but still had a poor command of it. Elsewhere in both countries some people could speak no other language than Tajik, or Kyrgyz, or their local languages and dialects. However, even people who don't speak Russian usually still understand it. Most people in Tajikistan understand Farsi, and in Kyrgyzstan — Kazakh, Uzbek and Turkmen languages.

paperwork and organisational issues

Except visas, no special preparation paperwork had to be done before the trip. Citizens of many western countries didn't need a visa for Kyrgyzstan. Europeans and Americans could obtain a Tajik visa upon arrival in the airport of Dushanbe. Along with a visa for Tajikistan people travelling the Pamir needed a permit for the GBAO (“Gorno-Badakhshan Oblast” = Mountain Badakhshan Province). It could be obtained in the capital, but since all expedition members had applied for their visas in advance at Tajik embassies in their countries, they got also the permit together with the visa. If your country isn't among those whose citizens are allowed to enter Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan without a visa, you should apply for a visa at their embassies in your country, particularly if you are going to cross the land borders. When applying for a Tajik visa, don't forget to request also a GBAO permit within the same application.

The entire border to China is fenced since the times of the Soviet Union. Now a fence is also between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. All together, hundreds of kilometers of wire fence! This picture shows a junction of the Tajik and Kyrgyz (white pillars) and Chinese (brown pillars) borders. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

The majority of the photographic attractions in the Pamir are within the Tajik National Park — one of the largest protected areas of the world. It includes most of the territory of the high Pamir and its boundaries aren't clearly delimited. There are no gates nor well visible signs indicating that you are in the national park. A payment for staying in the park is charged on daily basis. Tickets are being sold by the offices of the park in Khorog and Murghab, and at ranger posts in some villages at park border, i.e. in Vanj Valley. Travellers who entered the park territory without a valid ticket and ran into a ranger control, would have to pay around 100$ per day. Of course, you can claim that it was only one day and pay only 100 bucks. Another way may be to bribe the rangers paying less and not requesting a ticket.

The corruption in Central Asia is legendary. Many things can't be done at all without bribing a state official. However, many officials avoid demanding money and taking bribes directly from foreigners, but they will be refusing to do things anyway, and you would need to find a way how to pay them. It is easier when another local person, such as your driver, acts as a mediator. Our drivers told us also that they in fact paid money almost at every police and border guards station we were passing.

In some rare situations even offering a bribe won't help. Then it should mean that the official is indeed fulfilling an order that can't be avoided. This happened to us when we were going to Zorkul Lake. The border guards didn't allow us to continue our way and weren't able to give an honest explanation of the reason. Instead they were just trying to find something in our papers that would be a reason for denial a passage. When they didn't but still weren't letting us in, we gave up and went back. Later we heard from the locals that there was a military exercise in the area of Zorkul. Probably the border guards weren't just allowed to tell this to strangers.

safety and health

In the time when we were travelling Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan there were no serious dangers worth to be mentioned here. Now and then there can be outbreaks of civil unrest or war-like events in some regions, such as the GBAO in Tajikistan. Foreigners shouldn't be afraid of such situations but it may be worth to delay the trip accordingly, to avoid eventual logistic problems.

Cases of kidnapping weren't known from this region despite its proximity to Afghanistan and Pakistan. The border to these countries is almost impossible to cross in other places than a couple of bridges with official checkpoints. Therefore, the probability that a gang or a militant group from either of them would act in Tajikistan is extremely low. As usually in totalitarian regimes, the public order in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan is very well controlled by the state.

Thefts are possible in large towns and the capital. Therefore the usual precautions as in other countries with poor population should be used. Someone should stay in the camp when others are in the field. Fortunately there was always someone in our group who wasn't eager to move around much and was ready to play a guard.

There are also no dangerous infectious deseases in this area that travellers should be afraid of. The most serious hazard could be that of hepatitis A, but people who travel a lot in southern countries are immunised against it anyway. Of course, like everywhere in pastoralist areas, you should avoid drinking water from streams and lakes that may be contaminated with human or animal feces. It isn't difficult in places with such low population density and so many water bodies as Pamir and Alai.

A danger that is absolutely real and has to be taken serious is that of accidents and injuries during the work and trekking in the mountains. This terrain is really tough, and gets tougher with increase of the altitude. Being exhausted or altitude sick is a very dangerous condition, particularly when you are alone in the mountains. Often the danger can be prevented if you know in advance what your body can and have trained it. This time I had much less health issues although the altitude was similar to that of my last year's Ethiopia trip when I was suffering from altitude sickness. Though it is known that altitude sickness can't be prevented for persons who are prone to it, its impact can be somewhat compensated when the person is generally healthy and fit. Therefore, regular stamina training does make sense. Of course, some symptoms will appear in most persons. Most people will have difficulties to breathe, swollen faces, weakness, insomnia in the first week in the altitude above 3000m. I had this all too or observed in my travel companions also during this trip. Some of the expedition members appeared to be very sick in the first 10 days or 2 weeks, but were remaining active and continued to follow the planned route and work schedule.

The last but not least issue that should be mentioned here is sun protection. As always in the mountains at sunny weather the sunshine is very strong and contains very much UV radiation. Without appropriate protection your open body parts will get severe sunburns already within the first hour. This time I was using sunscreen creme for the face during the first week, till it got tanned, and gloves for the hands.

photography

The Pamir mountains and, to lesser extent, the Alai are not the easiest region for nature photography. Particularly, in the summer this is essentially a very dry and almost lifeless place. Good shots are very difficult to obtain, and it will require much time. To get more or less satisfactory results in this season plan with at least 2 or 3 very busy days at each location. Generally, I had been expecting difficulties in my work already before the expedition started and was afraid that even over 40 days of its duration wouldn't be enough because still too little time was planned for stays in each place. Nevertheless, almost complete lack of wildlife and extremely scarse vegetation in Pamir surprised and disappointed me.

The west of Pamir has very high mountains with steep stony slopes. Some peaks are over 7000m high. The rivers — Pianj, Bartang, Vanj — and many smaller streams are all coming directly from glaciers through relatively narrow valleys whose sides were covered at least partially by green vegetation even in this dry season.

The rest of the Pamir is essentially a plateau with average altitude around 4000m. The main ecosystem of the Central and Eastern Pamir is a mountain desert. The principal rivers — Murghab, Alichur, Pamir — are broader in their lower current and not so fast. Large parts of their valleys are wide and provide enough space for plains with pastures and fields. Three very large lakes — Karakul, Yashilkul, Zorkul — and many smaller are also in this area. The lakes are surrounded by a desert and stony hills.

The Alai Valley is bordered from the south by the Trans-Alai — the northern range of Pamir with Peak Lenin as the highest mountain — and from the north by the Little Alai — a mountain system that joins the Tian-Shan Mountains farther in the north. The Little Alai (or Kich-Alai) has much lower altitudes the the Pamir and the Trans-Alai that dont exceed 4000m above sea level. The Alai Valley is a broad plain that remains green even in dry months. The entire valley can be passed by car in less than 3 hours on a very good highway that goes all along it — from the east to the west. Like all large valleys in this region, the Alai Valley has a high density of settlements, and the natural landscape is almost entirely converted to pastures and agricultural fields.

wildlife

Unless it is a special subject, such as Snow Leopard, Tian-Shan Brown Bear, or Marco Polo Sheep, neither Pamir nor Alai are regions where someone should go with wildlife photography as main goal. In general, the biodiversity of Pamir and Alai is very low, and in the dry summer months even many of those animals and plants in the area can't be seen that indeed live in this region. For special subjects the season and travel destination have to be chosen with regard of their life and activity cycles. For instance, if it is known that Marco Polo Sheep can be easier found and approached in winter in Eastern Pamir, then a photographer has to go there in that season and have no other plans than only to photograph this animal species.

Some animals became rare or shy as a result of hunting and oppression by the activities of humans. So, not only singular but sometimes large heaps of dozens of Marco Polo Sheep skulls can be seen in the plains of Eastern and Central Pamir. The Marco Polo Sheep is the largest species of wild sheep in the world whose males have huge horns. Strangely, hunters don't collect the horns and appear just to leave them at the place where they have killed the animal. It is different with the Siberian Ibex whose horns are the desired hunting trophy, hence only males with long horns (1m and more) are hunted. Stuffed heads with horns are then shipped abroad by Tajik companies who organise hunting.

Of course, such hunting tourism companies can be helpful also to wildlife photographers. In this region, only in their private game reserves and with assistance of experienced trackers you can be more or less sure to find and to approach larger mammals for photography. In this expedition, I, too, chose this way, addressing a hunting tourism company that has a private game reserve near the state-owned Dashtidjum Forest Reserve. The Forest Reserve was depleted by poachers in the last two decades, and the wildlife that was supposed to be protected there, remained only in privately protected areas. Large populations of Siberian Ibex (Capra siberica), Tajik Marhor (Capra falconeri heptneri), Tian-Shan Brown Bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus), and Snow Leopard (Panthera uncia) are persisting within the boundaries of the private reserve that I visited during this trip.

My task in this expedition was providing quality images for subsequent popular and scientific publications by the expedition members and eventually for a publication of a specialised photographic account of this expedition in popular media. In the last case, we considered some spectacular photographs of wildlife as very important visual material, along with beautiful landscapes. I viewed it as the only chance to find and to photograph larger mammals in this season and in this difficult terrain, when it is a well-managed game reserve in a place with the maximum number of species. So was that place near the village Zigar and the Dashtidjum Reserve.

Since these people normally provide services only for wealthy foreigners, the prices were quite high also for a photographer — 300$ per day. 150$ they were requesting from a normal tourist. Before me only one Swiss photographer had been there, but already two or three times. Therefore I assume that they came to such rates through the experience with him. Maybe he was often making an impression that nature photographers earn a lot of money with their work. During my stay there I was doing my best to destroy this illusion.

This price includes absolutely everything — even airport pick-up — and with regard to the excellent service they provide and compared with similar offers that I know from Africa, even as much as 300$ may be appropriate. The reason why I nonetheless consider this price as too high is the quite poor availability of photographic subjects in this place. Indeed, the landscapes are quite spectacular, but to photograph them you don't need any assistance of locals and can stay in your own tent just anywhere. The fauna is not as rich as in Uganda or Costa Rica. If you would't find the only species you are looking for, there will be no alternatives.

This game reserve harbours healthy populations of many mammal species — Tajik Marhor, Siberian Ibex, Brown Bear, Snow Leopard, Asian Porcupine, Wild Boar, Long-tailed Marmot. Going there, I was hoping to have an opportunity to photograph at least one of these species despite bad season. Unfortunately, all our attempts to approach the animals were unsuccessful. My guide was the best hunter in this region and he was doing his best, but we could see the animals only from a very large distance. My primary subjects of interest were marhors and bears. We were seing marhors very often, but could not approach them closer than 300m. Although there were many signs of presence of bears everywhere, we saw only one female playing with two cubs in more than 1km from us. Also ibexes were visible only as spots even through a binocular. The reason of this failure was the very bad season. It gets too hot in July and August at lower altitudes, and too little green vegetation remains. Ungulates migrate therefore to higher altitudes in the mountains where snow is still remaining. Carnivores follow them. Bears normally spend the hot days in their dens. In this season they became completely nocturnal. My secondary subjet of interest were other mammals, but didn't encounter any. The nocturnal porcupines, who were very common but I was frequently seeing only trails and spikes that they had left back, but not the animals themselves, even when I was searching for them at night. Marmots were localised in this place to alpine meadows that I hadn't time to reach because I concentrated my efforts on ungulates.

A hut of hunters in the mountains near Zigar village where I stopped on my way to Fučik Peak for a rest (Click on picture to enlarge.)

The five days that I worked in the private game reserve in vicinity of Dashtidjum were a great time and a very exciting experience, but unfortunately, I failed to obtain the images of large mammals that I had come for. The hunters were explaining it with the wrong season. According to them marhors and ibexes are best to be photographed in the autumn, when they are in rut. Spring is also a good time for ungulates and the best for bears. The only period of the year with good chances to spot a snow leopard is in the middle of the winter.

Anyway I am absolutely sure that the results in other season can be much better. Unfortunately I hadn't been free to choose the season for this trip because it was an organised expedition that had other priorities. Therefore I decided to return to this place already next year in a better season and to repeat the attempts.

Since I had focused my attention on marhors this time, I already have some observations and conclusions to share. This protected area is home of over 300 marhors. Before it was established in 1997, only a little more than 30 were remaining. Now the population is already too big for this territory, but hunting remained strictly prohibited. The owners of the game reserve want to obtain a few hunting licences every year because rich people in the west and in Russia would pay huge amounts of money for a hunt at marhor. When I was visiting this place they were already expecting to receive the licences next year. Although I don't share that bizarre passion of some people to kill animals for fun, I understand, of course, that people who run the reserve need this to finance their enterprise and to provide better protection for the animal populations. Although marhors are currently among the most important prey animals of snow leopards, it is unlikely that hunting, if it would be allowed, will have a bad impact on the cats. My guide who is also the head of the family and the main owner of this place told me that there were already too many snow leopards in this area and that they would like to resettle a couple of them to other places if they would find any. Outside of protection areas, people often kill snow leopards regarding them as vermin. To reduce the potential conflict, adequate number of wild prey have to exist for snow leopards. Otherwise, they will kill cattle. Such places are few and usually only within protected areas.

In the place where I was, marhors hadn't been hunted for at least 15 years, but still appeared to be very shy compared to ungulates in other parts of the world that I had a chance to photograph. They see extremely well and can notice the slightest movement at least 500m away from them — a distance that hunters are already able to shoot an animal from. This is a source of misconception that the guides may have about the requirements of a photographer. Although I had told my requirements in advance, my guides were still thinking that 50-100m that I was talking about were an exaggeration. I don't know how that Swiss guy had been working, but I was surprised when they kept telling me that he hadn't needed to be so close to the animals as I was insisting all the time. However, it is obvious that to get a decent quality shot of an animal that is 1m high even with a 600mm lens a photographer has to be not further than 100m from it. Otherwise, the image would need to be cropped. The images that they were showing me, that had been made in this place by others, were shots just “for a record” — i.e. lacking an artistic component.

At least because I was there and maybe other photographers after me, the guides should already know how the requirements of a wildlife photographer are. The guides will, of course, do their best to reduce the distance between the photographer and the animal. Nevertheless, you have to be prepared that it will be large. An even more frequent reason of this isn't the shyness of the animals but a terrain that is impossible to cross. Often the animals and the photographer are at different sides of a gorge that is so deep and has so steep slopes that crossing it would require many hours of walk and climbing.

The issues with the photography of the brown bear are pretty much the same as with the ungulates — with one main difference: The bears may be easier to approach because they don't see that well. You should watch the wind direction, however — to avoid that the wind blows from you towards the bear. Since bears overwinter in dens, the time suitable for photography reduces to warm months of the year, but not to midsummer — when I had to be there. As I already mentioned: It was too sunny and warm; and the food plants of the bears were remaining only high in the mountains.

My attempt to photograph marhors (Capra falconeri heptneri) was this time unsuccessful. This photograph was made with 600 mm focal length from the closest distance that I could get at — around 300-350 m! (Click on picture to enlarge.)

For both subjects, ungulates and bears, a photographer would need the longest lens possible and use even it often with a teleconverter. The maximal focal length of my equipment was restricted this time to 600mm. For shooting at such big distance even this was too short. A very stable tripod or other kind of support is of course mandatory with such extreme focal lengths. Although you will have to carry the heavy equipment to the location, you will spend hours there hiding and waiting. This is a perfect shooting situation for use of a tripod. A gimbal head should make sense.

The area near Dashtidjum and Western Pamir offer opportunities for herp photography. Blunt-nosed Viper (Macrovipera lebetina turanica), Turkestan Agama (Paralaudakia lehmanni), Himalayan Agama (Paraludakia himalayna), Fedchenko's Gekko, Pevzov's Toad (Bufo pewzowi) are common there. A variety of large insects and flora are also good subjects for close-up and macro photography.

The bird fauna is rich at Dashtidjum and further in the west. Chukar Partridge (Alectoris chukar) is one of nice photographic subjects among birds in this area. Although it is being severely hunted, this bird is quite common. It can fly well but prefers to run on earth. Local people catch many hundreds of them during the breeding season using a calling male as decay. Some chukars may become even semi-domestic when they come to villages and live with domestic fowl. The you can photograph them from a very short distance. In Pamir and Alai the diversity of birds is much smaller: I counted not more than a dozen of bird species that I could spot during the entire trip.

Even compared to the Western Pamir, the flora and the fauna of the Eastern and Central Pamir are very poor. Rodents and hares were the only mammals that we were seeing more or less frequently. Among rodents the Long-tailed Marmot (Marmota caudata) was certainly a highlight. The adult individuals of this species are quite large and with bride red fur — quite colourful. People in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan believe that the fat of the marmots is a medicine and also find their meat tasty. Therefore they hunt marmots wherever they can. Nevertheless they are quite common in many parts of Pamir and Alai. This was the third marmot species I photographed in my life, so I had already some experience that I could apply to this subject. Basically the approach was like with the Alpine and Steppe Marmots: When the marmot escaped in a burrow it will soon come out again; you only need to sit still and wait. Interestingly, the marmots notice the least movement and immediately get in panic. If the object isn't moving, they don't perceive it as danger — no matter, how large and strange looking it is. This allows to place a remotely controlled camera very close to a burrow of a marmot. The best place for photographing marmots during this trip was Sasyk Bulak hot spring at Yashilkul Lake. Other good places were at Lake Horgush in Central Pamir and in Little Alai.

The Sasyk Bulak hot spring is also a place with very big population of Batura Toad (Bufo baturae). This species is known for its unusual karyotype: It has a triploid set of chromosomes. The ecology of these toads is not less unusual: They are diurnal and actively chase insects (also flying) even in bride sunshine in the middle of the day, when the ultraviolet radiation is particularly strong. The Batura Toad doesn't belong to visually attractive amphibian species, but due to its biological uniqueness it is another interesting photographic subject in this region. Bulunkul Lake and Issyk Bulag hot spring at Yashilkul Lake are other places with numerous populations of this species.

During this trip I photographed fishes for the first time. I didn't do it in situ, however. My subjects were specimens caught by our ichthyologist in the lakes Bulunkul and Karakul. For this purpose I had made a small aquarium and took it with me to this expedition. The lighting was provided with two flashes mounted on tripods and controlled via PocketWizard.

In Alai my main photographic subjects along with landscapes were also herpetofauna. Pevzov's toads (Bufo pewzowi), Siberian pitvipers (Gloydius halys) and Alai lidless skins (Asymblepharus alaicus) occured in the place where we were staying in Little Alai in vicinity of Daroot Korgon. All these species I photographed not only in natural surroundings but also on white — in a portable studio that I installed in my tent. It consisted of a light tent and two flashes on tripods, triggered via PocketWizard.

The main goal of visiting this place in Alai was search for the so-called “Turkestan Salamander” (Hynobius turkestanicus) — an almost mythological species of tailed amphibian that is supposed to live somewhere in this region, but also possibly never existed at all. Many herpetologists and amateur enthusiasts have been searching for it for decades — all in vain. So was our search, too.

landscapes

Everywhere in Pamir and Alai the opportunities of landscape photography are quite good. Some places are really spectacular and picturesque. With good weather and lighting very impressive landscape shots are possible.

I suppose it is needless to say again that midsummer isn't a good season for landscape photography in most areas of Pamir, particularly at lower altitudes. The sky is cloudless most of the time and the lighting is extremely harsh already soon after sunrise and the whole day long — till sunset. In higher altitudes the situation is much better: Clouds appear more often; it rains now and then, and can even snow.

Small mountain lakes are easier to photograph, and also the lighting may be better when such a lake is at high altitude. The banks of Yashilkul are too empty and dry, but still worth a couple of shots. Bulunkul is a much more beautiful place — particularly when clouds are running through the sky casting shadows on the mountains, or when the mountains are symmetrically reflecting in the water of the lake.

Karakul was the most colourful and scenic place that we visited in Central Pamir. We approached the lake from the south and spent a few days at a swampy terrain with small ponds and many springs and thin streams. In fact we didn't have a view at the open water of the lake. Nonetheless, already this place was absolutely fantastic for landscape photography.

The wide Murghab river valley is green even in the midsummer. From the road that goes along it to the town of Murghab you have a fantastic view at the valley. To get the best shots, I recommend to drive slowly towards the town from the pass during the sunset — starting from 5 pm.

From Murghab town to Karakul lake the road often goes along the Chinese border that is fenced. This area at both sides of the fence is completely wild. Though it is human-made, the fence doesn't disturb the natural landscape. Instead it is an interesting element that provides a little dynamics to this uniform and minimalistic scenery.

The mountains of high Pamir at altitudes over 4000m above sea level are very colourful due to rich mineral content. Absence of vegetation on the slopes lets the incredible variety of colours of the rocks and soil to shine through. Unfortunately, we weren't staying in such places but only passing them by car. I wished I had more time to photograph this wonderful scenery.

A similar effect can be found also in Little Alai where the mountains have a beautiful mix of red, green and grey. Together with flowers this resulted also an incredibly colourful scenery when the landscape was like painted. In this place I spent much more time and had enough opportunities to photograph at various lighting conditions. In Alai our movement was restricted by the absence of a car. Therefore we had to reduce the initially planned travel route to a stay at only one place with excursions around it. Therefore, landscape photography was my main activity. The Alai Valley and the surrounding mountain systems offer even more scenic views than Pamir.

final remarks

Since my return many people have asked me if I liked the trip and am satisfied with the results. I could not give them a definite answer. Despite some disappointments during the trip, I have a very positive feeling about this time. I think the most valuable result for me was the participation in this expedition because I had never planned to travel to this region myself. Therefore this expedition was a great opportunity for me to explore Pamir and Alai. Since I don't plan to repeat this trip in future, I am regarding it as a lifetime experience, and am grateful to the people who made it possible.

As always when I am travelling, I learned very much and gathered new impressions and experience. A large portion of them I reported in these field notes that were intended both as a memory record for myself and as information resource for other photographers wishing to travel this region. For them here are the most important recommendations in brief:

- Don't go to this region in the period from late June to early September. The best season for general nature photography is from late April to the middle of June. Early spring is also a good time but you may have difficulties with crossing some remote areas by car, particularly with crossing rivers. The period from October till December is perfect for ungulate photography, and December-January — for snow leopard and dramatic winter landcapes. Late March and early April are good for photographing ungulates and bears in western Pamir and Dashtidjum. Anyway, as I already mentioned, if you are a nature photographer, going to Central Asia in one of two peak seasons of the year — in the second half of summer and second half of winter — is a bad idea.

- Hire the best driver and car you can find. Ensure that the driver has experience with work in the mountains and knows the area you are going to.

- When going to central and eastern parts of Pamir, take enough fuel both, for the car and for cooking.

- Have the best tent you can afford.

- Don't choose the airlines by the cheapest ticket offer only. Look at the luggage prices, too.

- Don't plan such a long route even if the trip is going to last for 6 weeks. Make two long trips instead — one to Pamir, and one to Alai.

Although the season wasn't perfect for photography, I shot many good images of landscapes and even of wildlife. Some of them were for the time when the expedition ended probably among the best of this region. If they once get published, I would regard this trip as absolute success.