field notes

ethiopia, 2012

Despite its overpopulation and huge scale of devastation of natural resources and landscapes, Ethiopia may still be an attractive destination for a wildlife photographer. It is a very large country with many types of climate and geological relief. Due to these factors, Ethiopia's flora and fauna are also very diverse — ranging from desert and grassland ecosystems to afroalpine communities of highly specialized and often endemic species. In many areas, the remains of this rich biodiversity are now formally protected but still under increasing pressure through population and economy growth. Since the governmental efforts in Ethiopia, as in most parts of Africa, are targeting more reduction of poverty and building country's infrastructure than conservation and sustainable management of natural resources, it is to expect that the situation of wildlife won't improve. Also we should expect that the negative change of landscapes will continue as a result of road construction, growing agricultural use and urbanization.

Thus, as I always conclude in such cases: We, nature photographers, have to hurry to capture in our pictures the vanishing wild nature. Unfortunately, this applies to Ethiopia probably even more than to other Eastern African countries.

Ethiopia is so huge that even a decade of trips wouldn't be enough for visiting and exploring all its natural sites. I have returned from my first expedition that has covered only a very small area in the south of the country, and this is my report about it. Certainly, I will travel again to Ethiopia and even to the same area because I don't feel that I have explored it adequately. Now I don't know how many trips I am going to undertake — for sure not less than 2 or 3. So, further reports will follow.

planning and preparation

As always with such trips that I organise myself, I started the preparation about a year before departure with studying books and publications in the Internet. First I had to decide where in Ethiopia this my first trip should go. I was considering two alternatives: The north and the south. In the north, I was thinking about combining a week in Danakil Depression — for landscape photography — with two weeks in Simien Mountains — for photographing geladas, ibexes, wolves and other wildlife. In the south, I was interested in forest and in afroalpine fauna. After I learned more about Simien Mountains and Danakil, I realized that I would need at least a month to cover both locations in only one trip. Since I have only up to 5 weeks in a year for tavelling, I didn't want to spend all this time in Ethiopia. It was obvious to me that for the best results only for these two destinations in the north I would need at least two separate trips.

In the south of the country I was interested mainly in forest herpetofauna and, of course, in photographing the Ethiopian Wolf that is more common in Bale Mountains than elsewhere. Unfortunately, there was a similar problem of combining both in one trip. Reptiles and amphibians that I was wishing to photograph live in moist and relatively warm forest habitats at lower altitudes while the wolves live in highlands — in cold climate and on plains with afroalpine vegetation. Like Danakil Depression and Simien Mountains, these two habitats in southern Ethiopia are separated also geographically: There is a large distance between them. Also here I had to choose only one destination. As usually, I was torn between herping at not so spectacular places and photography of iconic animals at iconic locations. First, because I generally disliked photography of popular subjects, and second, because I prefer photographing reptiles and amphibians over other animals, my initial plan was just to go herping. However, it had to be a nice nature site where landscapes and wildlife are more or less preserved.

When I was looking at distribution maps of herps and even of birds that I was planning to search for in southern Ethiopia, I saw that almost all of them did not live in the only national park in that region — the Bale Mountains National Park (BMNP). Only two animals of my main interest could be found there with enough reliability: the Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis) and the Bale Mountains Vervet (Chlorocebus djamdjamensis, or Cercopithecus aethiops djamdjamensis) — the so-called, “Bale Monkey”. Some animals of my second priority lived there too: Mountain Nyala (Tragelaphus buxtoni), Menelik's Bushbuck (T. scriptus meneliki), Stark’s Hare (Lepus starki), endemic rodents (Tachyoryctes macrocephalus, Dendromus lovati, Arvicanthis blicki, Megadendromus nikolausi, Stenocephalemys albocauda, Stenocephalemys griseicauda and some others). Also the landscape with afroalpine flora were looking very promising. But the chances to find amphibians or reptiles were uncertain. Among them, the animal of my main interest in Ethiopia was the Ethiopian Mountain Adder (Bitis parviocula) — a large and colourful viper that is endemic to Ethiopia and whose photographs in situ are very rare. Although this snake is being bred by herpetoculturists in Europe, America and Australia, it is very little researched in the wild. The scientists had repeatedly collected it only at a few locations in the south-west of the country. That this species can also be encountered in the area of Bale Mountains has never been confirmed by official findings since only one specimen had been brought by Danish scientists and reported to be collected at Dodola vilage — in the north west of Bale region. Nevertheless B. parviocula was on the list of herpetofauna of Bale Mountains National Park (see it on the website of the BMNP — Bale Mountains Conservation Project : Fauna). On this list I also saw some other interesting endemic reptiles, such as Chamaeleo balebicornutus, Chamaeleo harennae, Lamprophis erlangeri. The park office was also claiming that 17 species of amphibians lived there. Regarding all this, I decided to try my luck in the Bale Mountains area — to combine herping and popular photography.

The other big question was — when to go. I knew that the Bale Mountains were a cold area, and that a rain season in the highlands could be the most unpleasant and least productive time. On the other hand, on lower altitudes, it is usually the best time for herping. There are two rain seasons in Ethiopia — longer season of heavy rains in the autumn and little rain period in the spring. Travel guides and websites about Ethiopia were praising the winter in the Bale Mountains, i.e. the dry season after big and before little rain season — because it is the warmest time of the year — when “the sky is clear, with many stars”. The period from October till January is the birth period of the wolves. Certainly these months, when vegetation is green and many plants are blooming, should be the best, but strangely various information sources that I was using were claiming that any time of the year was good for visiting the Bale Mountains. (As I had to learn later — during my trip, such statements were wrong.) I also had been told that the best chances to find Bitis parviocula were from March till August, but didn't know then that this applies only to moist forests in the lowland. Hence, I decided to go in late February and stay there till the middle of March because I was thinking that the little rain season would start in March and that the weather would be suitable for herps. At the same time I underestimated the speed the pups of the wolves grow and that they are being born actually in the autumn and by the end of February are at least 3 months old. Therefore, I was expecting the wolves with their young still to be there in February. After all these estimations and considerations I finally scheduled my trip for late February and the first half of March and proceded to preparation phase.

First I had to decide how long I would need a car. Basically, the question was: Should the car only bring me there and back to the airport, or will I be using it all the time? To know this, I had to plan the route more or less detailed. I was considering a few options — for instance: 1) to go by car to Dodola village which is to the west from the BMNP and from there trek through the mountains towards the national park; 2) to go to Dodola and from there also by car — to the south for herping, and after that, also by car — to the BMNP, for the wolves; 3) to go to BMNP and to drive around the park to the south where to go herping, then return to the park and look for the wolves... To organize my trekking in Bale Mountains I tried to contact organisations in the region who were specialized for this for foreigners — Dodola Tour Guides Association, Adaba Tour Guides Association, Nyala Guide Association (via Bale Mountains National Park headquarters). Although they all had nice websites where they were giving e-mail addresses for contact, none of them answered my mails. I decided not to call them because, first, I was not sure that their English will be adequate for conversation on phone. Second, I was afraid that unnecessary misunderstandings would emerge that make everything even more complicated. Third, and most important, I always make arrangements in written text because I prefer to have a confirmation that everything is clear for both sides and agreed.

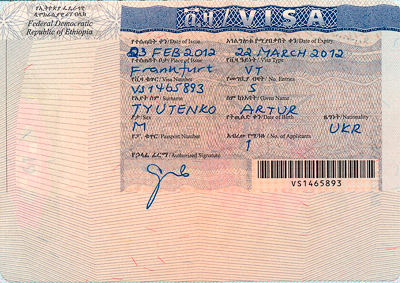

If you are a lucky citizen of a country that is on the Ethiopian list of "tourism-generating" countries, you can get a visa upon arrival at Bole International Airport of Addis Ababa. Otherwise you'd need to apply for a visa at an embassy of Ethiopia in your country and get such a sticker in your passport. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

Asking people who had travelled Ethiopia didn't help much because there was nobody who did it like I was planning — staying for long in a certain area. Typical tourists just went to Bale Mountains National Park by car or by bus and spent a couple of days there — watching wildlife near headquarters or near the automobile road that is crossing the mountains. The answer was usually: “Most likely you would need the car all the time.” Many people were also reporting about their troubles with Ethiopian cars and drivers: the car were in bad technical condition, the drivers not reliable... People were meaning with this that there is a danger that the car wouldn't be on time, or even wouldn't come at all if you have arranged a pick-up. Hence, it should be better to keep the car for the entire trip. Likewise, asking around and looking for information about Harenna forest was also without result. All people that I contacted, were writing back that they had only a short trip there by car. No one had trekked in the forest.

The less information I was finding about my travel destinations and the more controversial it was the more curious I was becoming. Finally I decided not to make any arrangements in advance but just to go there and to see what I get.

getting there and moving around

This is my luggage on a cart in Nuremberg Airport. (Sorry for the crappy image quality from my Blackberry.) I had two full 140 l and 85 l waterproof expedition sacks, a waterproof case, and a small camera bag. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

When I was going to book a flight to Addis Ababa, I checked the offers of all airlines that were flying from German airports to Addis Ababa — namely, Ethiopian Airlines, Lufthansa, KLM, and Turkish Airlines. Ethiopian Airlines and Lufthansa were flying from cities that were quite far from my home, and their tickets were about 25% more expensive, than of the Turkish. Turkish Airlines were offering flights over Istanbul from my home airport, Nuremberg, but had a very low limit for luggage — 1 piece of checked luggage of 23 kg weight. For each kilogramme exceeding this they were charging 20$. Since I was going for a long expedition and had to take camping equipment, enough cloths and much other stuff along with my heavy photographic equipment, I was expecting the total weight of my baggage to be well over 40 kg, i.e. there should be two pieces of it, about 20 kg each. The price of return ticket of Turkish Airlines was only 405€. The ticket of KLM that was also flying from and to Nuremberg was only 100€ more expensive, i.e. as much as only 7 kg overweight in Turkish Airlines would cost. With 20 kg more that I was going to have, the flight by KLM from Nuremberg via Amsterdam was becoming cheaper. Therefore I took it, and as in my previous trips, again I flew to Africa by KLM.

The Ethiopian are the largest airlines in Africa. They have a well developed network of domestic flights and airports throughout the country, but no flight was available to my destination, nor there was a public airport. When I travelled there, the Bale Mountains National Park could be only reached on road. In Ethiopia, most cities and towns have good bus connection, and many back packers prefer to travel by public bus. In my opinion this may be a good way to travel only for people with little luggage and much time. A busy photographer with a lot of expensive luggage should prefer a hired car. So did I.

Theoretically, at least in dry season, one can go to Bale Mountains by a city car. If you aren't planning to drive in the national park or anywhere on unpaved roads or off-road, you don't need a 4WD. Most paved roads in Ethiopia can be passed by a normal car. Both roads that go to Bale region from Addis Ababa were new and in excellent condition. If I knew this and if I were sure that I wouldn't use the car as transport in the BMNP, I had looked for a city car to bring me there and to take back. Such a car should cost less in two ways: You pay less for rental and for fuel than if it is a 4WD vehicle. Since I know the road and the situation now, I may try to hire a normal car when I will be going next time to Bale Mountains. However, there is no evidence that a driver who only drives in Addis Ababa would agree to go with his car more than 350 km away from the city. Next time I may try to find one, and chances may be good, considering the low level of income of people in Ethiopia, but more likely I would call the driver that I met this time.

I started my trip with walking the streets in the capital and asking for a 4WD car. I found a driver with a good Toyota Landcruiser. His offer wasn't cheap, but the driver was very experienced and professional, and the car was good. Although many Ethiopia travellers report the opposite, my trip began with the positive experience — that cars in this country are in good technical condition and drivers are reliable and professional. Maybe it was luck, but I am inclined to think that it was because I wasn't looking for the cheapest offer. Instead, having a nice and reliable person at my side was more importent for me and I never regretted paying a couple of euros more for it.

It is possible to go by car across the Sanetti Plateau in Bale Mountains National Park towards Kenya. This is how many tourists visit the BMNP. They come to park head quarters at Dinsho village, stay for a couple of days in a hostel (called "lodge") and visit Sanetti Plateau and even Harenna Forest by car from there. Alternatively people can pay single-day visits in the mountains and forest by car from nearby towns Goba or Rone. Also for someone with more profound interest in Harenna Forest, it is better to go there by car and have the base in Rira town or at so-called Katcha, a clearing in the forest which is an officially assigned campsite. If I would be going to explore the Harenna Forest some day in future, this is how I would skip visiting the mountains and save time.

For someone who is interested mainly in the mountains, Dinsho is the perfect starting point. From there it is possible to come by car as far as Web Valley and Kotera Plain — on the roads that were made by researchers' cars. Certainly, a 4WD car is necessary for that, and in a wet season even it can get stuck in mud. I didn't know about this road at the beginning of my trip, and sent my car back to the city having arranged that it will come back for me to Dinsho on a certain day. On the other hand, the Web Valley can be reached by foot in only a few hours, so driving there makes sense only for someone who plans to go only to this area, to stay for some time there, and to return to Dinsho. This was not my plan, and using the car just one day more didn't make much sense.

Apart from carrying the luggage yourself, the only other transportation means on the most territory of the park is the horse. There are riding horses, but they are small and skinny, and may be not suitable for a tall and heavy person. Typically, horses are used for carrying the luggage. I have been told that the norm is up to 40kg per horse. According to the rules, each horse has to be accompanied by a so-called “horse assistant”. Since for carrying the belongings of this person also a horse is needed, in reality, there is always one horse more than the number of horse assistants. The number of horses grows very quickly with the number of people who go for trekking in the mountains. It also depends on the number of days the trekking should take. To provide my being in the mountains with all necessary logistics for 19 days, 4 horses were necessary.

accommodation

Booking in advance a hotel room for overnighting in Addis Ababa is neither possible, nor necessary. None of midrange hotels that I attempted to contact from home answered my mails. As I mentioned above, I prefer written communication. After reading a travel guide and asking around on forums I decided just to go directly to a hotel of my choice upon arrival in Addis. It looks like to get a room in a decent hotel in Addis Ababa is never a problem. There are many inexpensive hotels, but unfortunately prices increase almost every year while the quality of rooms and service remain poor — measured at European and American standards. Anyway, in Germany, you can have a better bed and breakfast for the same money. Don't complain! You are in Africa — this explains it all. It is not what you may be thinking... According to “development” logic, people are greedy in the West — in Africa they are poor.

some of my camps in bale mountains national park

Dinsho camp: The BMNP head quarters has a hostel (a.k.a lodge) and a campsite where you can pitch a tent. Days are hot there, and I put my tent in shadow under a tree. Beware of warthogs near park HQ — don't live your tent unattended. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

“Habera Camp” in Web Valley — at Finch 'Abera waterfall. In the little gorge that is visible in the background I have collected two tadpoles of a species that I didn't know. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

Hoarfrost like on this picture taken in Keyrensa Valley is common in the morning at altitudes above 3500 m above sea level. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

The night in Rafu Valley was for me one of the toughest experiences: It was chilling cold and windy. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

“Katcha” means clearing. Indeed it is a huge clearing in a pristine Hagenia forest made by beekeepers families who live in this place — very sad picture actually. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

“Tohu” is the name in Oromo language for any overnight on the way. The guide just finds a suitable place for camping. We had two such stops, and both were at Harenna Escarpment — among heather woods. Both times it was an unpleasant stay: The place was dusty and almost lifeless. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

On the way in Bale Mountains the only roof over your head is that of a tent. Not all local people who will be accompanying would have one. Then they sleep in huts of pastoralists that are found almost everywhere in the mountains, but I wouldn't be able to do the same because this kind of lodging is extreme even for African standards: I hadn't seen nowhere else in Africa such unpleasant sleeping places as those huts. Unless you have lost everything and are struggling for survival, I am sure, you would prefer a tent. So, bring your own from home, or rent on in Addis Ababa, or ask the park office for a tent to rent. The first option is better because tents are rare in Ethiopia. As an outdoor photographer or nature traveller you would anyway have a tent that you use elsewhere, so it would be a good idea to take it on such a trip like mine. Since tents are difficult to purchase in this country, it is a good gift to a dedicated helper, for instance, to your guide. I had bought an inexpensive 3-persons tent specially for this trip, used it in Bale Mountains for myself, and gave it the guide who had done really a great job. He preferred to take the tent as tip — not money.

When choosing a tent, bear in mind that it has to be large enough to accommodate you and your luggage. In Bale Mountains there are no people nor animals who would steal your stuff, but anything that you leave outside will get dirty during the day and wet in the night. Therefore it should be a good idea to keep as many items as possible inside the tent. (At Dinsho, however, you have to do it also because of wildlife, particularly warthogs.) A 3-person tent with a footprint of 2 x 2 m that I had for me alone and my luggage was not too big. For photographers, a tent should be at least twice as large as the number of people who are going to sleep in it, i.e. for 2 persons a minimum 4-person tent would be necessary. You should remember this also when you are planning to rent a tent. Since all tents that I saw there were for 2 persons, if you are a photographer, you would need such a tent only for yourself and your stuff. If several photographers are travelling together they are likely to need 1 tent per person.

Obviously, the larger the tent the heavier it is. The weight of my tent was around 3.5kg. However, it wasn't an issue because the tent was carried by a horse. If I had to carry it myself, I would have chosen a lighter (though more expensive) and smaller (2-persons) tent.

Although it is tropical Africa, the low temperatures in the mountains shouldn't be underestimated. At altitudes above 3,500 m a.s.l. frosty nights are usual even in one of relatively warm months — February. In the morning hoarfrost covered my tent and grass around it — even in Harenna Forest where lowland animals such as lions live. I was told that in the autumn nights are even colder. Since I didn't know how the temperature will be in Harenna Forest, I assumed that I would need a not so warm sleeping bag for this area. Since I had two sleeping bags for temperature 8 - 12 °C at home, I took both to this trip — to sleep in one bag if it would be warm and otherwise to put the second bag over it. In reality it was so cold every night during this trip that I was sleeping in two bags, and had a warming suit on my body and a fleece cap on my head. Now, I think that it should be better to have only one sleeping bag for temperature up to -5 when I go there next time.

Also the air is cold in the night in Bale Mountains, the ground isn't. I was sleeping on a self-inflating mat that was 2 cm thick. I brought it from home too. Mats and sleeping bags may be rented in Ethiopia but I wouldn't rely on it. In travel reports that I read before the trip, tourists were complaining that sleeping bags provided by tour organizers were not suitable for the cold climate in the mountains.

The campsites in Bale Mountains National Park are just places near water sources that guides know about. Camping at a dedicated place is not mandatory except Dinsho. At BMNP headquarters at Dinsho there is also a hostel called “Dinsho Lodge”. It has running water, showers and power supply. This lodge is a good place for rest after trekking and I took this opportunity, too. After 18 days of sleeping in a tent it was very pleasant to lay myself on a bed.

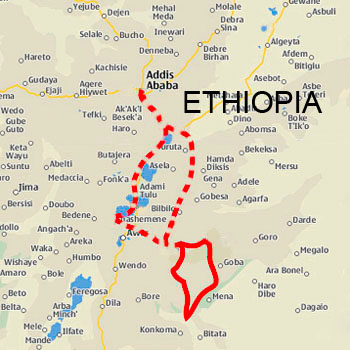

the route

I went from Addis Ababa to Dinsho by car via Adama, Assela, Asasa. The way back was via Shashemene — with a stop for one night at Langano Lake and a visit in Abidjatta-Shalla National Park. The trekking in Bale Mountains National Park started and ended at Dinsho and took 19 days. Below you see a map of this route.

Unfortunately the route was too long for the time available. At the beginning of the trekking I spent several days in Web Valley (Habera Camp), in Keyrensa Valley (Keyrensa Camp) and in Harenna Forest (Katcha Camp). The average daily walk distance was around 17 km. The relief is with hills that you have to go up and down but there are no high mountain slopes that you have to climb. Nevertheless, the walk may be quite exhausting at this altitude — particularly for a photographer who is carrying heavy equipment. The maximum distance on one day was around 23 km — between Habera and Keyrensa camps. Usually we arrived at the destination in early afternoon, and I had a couple of hours for photography. Although I was very tired, I didn't want to lose time and tried to find as many subjects as possible around the camp before it gets dark. Photographing on the way was also possible but usually that were the hours when the light was bad. Overall, the days when I had to change the location were the least productive. Unfortunately, most days on this trip had to be so because we were in a hurry to come back on time.

In Harenna Forest the stay was already too short, and we had to leave after just 2 nights. Only one whole day is much too little time for a forest area where animals are difficult to find and to approach. As I mentioned above, it was a big mistake of mine to combine the visit of afroalpine areas with the visit of this place. The Harenna Forest is simply too remote if you walk there from Dinsho. If I ever go there again, I would do it by car and stay for at least a week.

After two nights in Harenna Forest, the rest of the trip was only the return: At each place — Humburi, Garba Guratcha, Worgona, Danka River — I had only one night, one afternoon and one morning. This is enough just for seeing the place, if I were a tourist, but too little time for photography. Of course, I did some good shots but it was very disappointing not to be able to choose the time that would be more suitable for certain subjects.

logistics

Since I organised this trip myself I had also to provide all logistics for it including personnel, pack horses, food and water supplies, fuel for cooking, electric power for my equipment, etc. I had also to make all necessary payments to the park office and to people who were working for me.

organisation

Most tourists come to Bale Mountains either to spend only a couple of days at Dinsho and to watch mountain nyalas and other wildlife around the park office, or for 4 days or longer trekking organised by tour companies that normally reside in Addis Ababa and bring the tourists from the city to the national park from there. In my case, I had first to prepare everything myself for three weeks in Bale Mountains and Harenna Forest — to hire people and horses, to purchase supplies, to pay permits... Though I had no concrete plan how to do it before I came to BMNP head office, organising everything necessary there was quite straightforward. Men in the park office appear just to hang around most of the time, not being very busy. If any vistors arrive, they sell permits and give them a guide. In my case it was almost like this too — with only that difference that I had a longer talk with them, to plan my trip in the park. It also became completely clear to me that these people are of little help for someone with special interest. They may advice a tourist what to take on the way and where to go but they weren't able to answer my questions about other wildlife than a couple of species that tourists usually come to see. They confirmed that the route that I had planned was realistic. This was also wrong — as I had to find out later. If they had told me in this first conversation that I would need more time at each location, I would have changed my plans accordingly. I was also surprised that they didn't know about amphibians and reptiles in their park although 17 species of amphibians and some lizards and snakes were listed on their website.

The park officials introduced me the guide who was also in their office at this moment. Everything was as if they all had been waiting for me. That is quite understandable — when people have actually no other job than awaiting visitors.

The park officials calculated together with the guide the expenses for my trip. I paid the amount due for paying at park head quarters, i.e. the entry and camping fees for total duration of my stay in the park. Like in any office in East Africa, you have to pay cash at BMNP office. When I arrived at Dinsho I had less than 15,000 Br left from about 24,000 Br that I had got at a bank in Addis Ababa. To pay all bills for staying in the park for 19 days I needed more cash than this. It was Friday afternoon, and the local bank office was already closed, hence changing money at Dinsho wasn't possible anymore till Monday. Fortunately, the guide agreed that I would pay him and other people not the whole amount before the trip but only a part. After the return, I would change my euros in a bank and pay them the balance.

The guide accompanied me to the camp where I put my tent. Then we discussed a rough itinerary of the trekking. Certainly, it isn't possible even for an experienced guide to anticipate everything and to plan every detail for so many days. Though the guide knows the terrain, fauna and flora, and the habits of the animals that you are looking for, but he can't guarantee exact fulfillment of the plan.

The next day in the afternoon the guide came with three other people to the campsite. These people were a cook and two horse assistants. His first estimation was that three horses will be necessary for the trip. But the next day, when the horses were packed, it became apparent that the calculation had been wrong: An additional horse was needed to carry the supplies and the belongings of the horse assistants. The guide explained me that according to the rules established by the local organisation of horse assistants, the number of horses had not to exceed that of horse assistants plus one, i.e. 2:1, 3:2, 4:3, etc. (However, I'm afraid that this rule wouldn't work for large groups of travellers — when just one more horse wouldn't be enough.) As I already mentioned, a horse is supposed to carry maximum 40kg of load. Hence, with my almost 60kg of luggage, I alone needed 2 horses. One horse assistent had to take care of them. But since we were going to spend 17 days in the mountains, we had to take food for us and some forage for the horses accordingly. The guide and the horse assistent had also their own tents, cloths, etc. Hence another horse was necessary to carry all this. Since that were already 3 horses, another horse assistant was required. He also had some personal stuff to be transported, and, of course, we needed some more food.

On my way in Bale Mountains I was accompanied by 6 people and 4 horses. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

Since we were 4 persons now, someone had to prepare our meals. A traveller who goes for a short trekking only with a guide and one horse assistant can probably cook meals himself. But if there are more people, either someone has to “play a cook” for all or there should be a special person for that task. During that trip, neither myself, nor the guide, nor anyone from the horse assistants were ready to prepare meals for everybody. Therefore, I decided to hire a cook, and asked the guide to find one. To my big surprise he came with a young lady. I had not expected such liberties for women in this region where the majority of population were Muslims.

Together with the cook, we were 5 people, so three horses were not enough. This became clear in the morning of our departure from Dinsho. Luckily, hiring another man with a horse wasn't a problem. Of course, I couldn't mind when a trainee of my guide joined our troop. All together, my support team consisted of 6 people with 4 horses.

You may be asking if they weren't too many to pay for, if all those 6 people were really necessary for this trip to be a success. I still have no definite answer for this question. Since I don't know in depth the culture of these people and all details of their relationships, I have to agree that the role separation was right for them, i.e. that a horse assistant couldn't be a part-time cook, or the guide couldn't be looking after horses. Certainly, fewer people doing more work would be eligible for a better payment. But this may be just our Western approach, and the sense of efficiency may be just different in other societies. I assume that there are people who would let also others earn money instead of trying to do other person's job in order to get a maximum payment. If people who were helping me on that trip had this honourable attitude to each other, I certainly respect this. I also enjoyed the company of these extremely friendly, modest and reliable people and am very grateful to them.

food and water

For a traveller in Ethiopia getting food is usually not a problem, though some parts of this country and its closest neighbours — Somalia and northern Kenya — serve for headlines worldwide due to almost permanent hunger crisis. In Addis Ababa and in towns throughout the country there are plenty of restaurants with international and traditional Ethiopian food. Meals are usually quite tasty and also inexpensive — compared to the prices in European restaurants. If you are going very far from cities and big towns, it is better either to make arrangements for food supplies in advance at your destination or to provide your own supplies. I did something in between: I purchased some rice, noodles and canned meat in a super market in the capital, but not everything necessary because I didn't know for how many people and for how long I would need such supplies. What I had would have been enough for me alone for 10 days, and was going to get the rest on location.

According to travel guide books and to what people usually write in discussions on Internet forums, guides, horse assistants and other staff members during trekking in Bale Mountains and elsewhere in Ethiopia, are self-sustainable, i.e. the travellers are not supposed to provide not only accommodation for them but also food. However, usually the travellers share food with all their trekking companions. Personally I had been initially planning to pay for food not only for me alone but for everybody in my supporting team. When I did it, I noticed that they considered this as a norm: The guide and the cook did all calculation of the demand and requested payment for the entire supplies for all 7 people in the group. They did not attempt to ask my agreement, i.e. they were doing as if it was a rule. In that sense, the information in books and on forums isn't reliable.

When I can get wine, I prefer it to other alcohol drinks. Ethiopia is one of few African countries that has own wine production. Although it isn't a premium quality and tastes not great, I found Ethiopian wine okay, and ordered it in restaurants when it was available. The most funny thing about it was, that it was sold and served in beer bottles. The wine on this photo (taken with my Blackberry smartphone) that I drank in my hotel in Addis Ababa even had got a prize at an exhibition in German Democratic Republic. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

In Addis Ababa food in super markets may be almost as expensive as in Europe, but its variety is much smaller. In such remote regions as Bale Mountains you can buy only a few kinds of food ingredients — usually rice, spaghetti and noodles, ketchup, honey, marmalade, sugar, spices, solt. In Bale Mountains you won't get fish, although it lives there and fishing is offered as recreation for tourists. Strangely, meat also appears to be a problem despite the fact that local people are cattle breeders. There is, of course, no tradition for making cheese. Although huge numbers of sheep, goats and cows are kept by them and the mountains habitats suffer overgrazing, it looks like people in this area do not regularly consume meat. In all 19 days of my travel in Bale Mountains, I haven't seen anyone eating meat or drinking milk, and no one was meat or milk for sale. It is possible, however, to purchase a small sheep (actually a lamb). But, it would make more sense if you are tavelling together with at least one other person who would share costs with you. The sheep would cost about 30-35€ and would be so small that the meat would be enough only for one meal of your group. Certainly it is not a huge expense measured on European or American prices, but in Ethiopia it is much money that you may need for other payments.

Although water may be scarse in some regions of Ethiopia, in Bale Mountains it isn't. It is available at all altitudes but not everywhere is clean. The daily trekking route goes usually through several places with drinking water but you should never rely on it. The guide knows such places but the condition of the water depends very much on weather, season, presence of cattle, etc. Therefore you may find it muddy or dried out when you have reached the place. Always take enough water for drinking on the way — about 1.5-2 litres. Also the camps are typically situated at small rivers or even springs. Spring water is usually good for drinking without treatment. Particularly at high altitudes of the Sanetti Plateau you can be sure to get clean water directly from a spring. At other places the water would have flown long distances over areas contaminated with cattle dung. The locals may drink it nevertheless untreated but I hadn't. I used a water filter Katadyn Pocket to prepare water for drinking, washing hands and face, and for brushing teeth. I found also that having the Katadyn filter everywhere with me was more practical than carrying drinking water: The filter is not heavy, and you can made as much water as you need at every place. The original condition of water doesn't matter: It will be always perfectly clean after it has run trough the filter. Since I had to clean the filter many times during the trip, I suppose that the water was dirty not just in my imagination. Even when you stay in a hotel, with a water filter you can safely use the tap water for drinking and brushing teeth.

For treatment of water with filter I was using a foldable plastic canister. It had a tap and also served me as reservoir for water that I used for washing hands and teeth brushing. I stored drinking water in a See-to-Summit water bag that I found very reliable and convinient. For cooking water from rivers and springs was used without filtering. Horse assistants were bringing it in a large canister to the camp.

Local people appear to use only firewood that they gather everywhere in the mountains. My horse assistants, cook and guide didn't want to use the Primus stove that I brought from home and the kerosine that I had bought before the trip because they needed a fire not only for cooking but also for warming themselves. On this picture, my team is sitting around such a fire in Web Valley. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

In guide books and on forums you may also come across advices to bring a kerosine stove and fuel. This may be true for other regions of Ethiopia but not for Bale Mountains. I had brought a Primus OmniFuel stove from home and purchased 5l of kerosine at a petrol station on the way from Addis Ababa to Dinsho. At the end, I had to give away almost all the kerosine to people at Dinsho because we didn't spend a single grop of it during 17 days of trekking. I myself used the stove just three times at Dinsho for preparing tea. The Primus OmniFuel is very efficient, and I needed very little kerosine to get a litre of water in a pot boiling within a few minutes.

At every campsite horse assistants gathered dry wood and were maintaining fire almost constantly, as long as we were staying there. They were warming themselves at the fire and cooking. Since the omnipresent pastoralists also use wood for making fire, I was surprised that some twigs and logs had still remained for us.

The daily menu was the same all 17 days of trekking in Bale Mountains: a pita bread with marmalade — for breakfast, rice or noodles with canned onion-and-tomato sauce — for lunch and for dinner. Sometimes, I got a pita bread with marmalade also for lunch — when we hadn't reached the next campsite yet. Normally, I like pasta — noodles, spagettis, etc. — but I couldn't see it anymore for at least two months after my return home. The only drink — except water — was tea. In the homeland of coffee, I drank coffee only in my hotel in Addis Ababa, in towns on the way back from Bale Mountains, and in a great coffee shop in Addis — before my flight back to Europe. All 19 days in Bale Mountains, there was tea — three times a day.

Someone who can't stand such cuisine is advised to hire a professional cook in Addis Ababa who would know how to prepare better meals and make a more varied menu. This is really an option that is worth to be considered particularly for larger groups. My impression was that the lady whom I hired in Dinsho for this trip only new how to boil water for pasta and rice. She couldn't even bake pita bread: A horse assistant did it. I suspect the reason for this in shortage of food supplies in this region. This time the problem was not the availability of ingredients, for I could bring everything necessary from other places, but the typical cuisine in this area of Ethiopia: People just got used to such scarse meals and don't think of anything better.

Fortunately, I had also some food only for myself. The canned meat that I had bought in Addis Ababa before the trip was pork. Actually, there were no other options in that shop, and I bought those meat preserves that were available without paying any attention at the kind of meat. In Bale Mountains people in my support team were Muslims, hence they refused to eat them. This was, of course, to my benefit. Eating this meat compensated me the loss of energy that I could not otherwise restore with the daily food that contained almost no proteins.

From home, I brought a dozen of energy bars. I ate one a day at most physically challenging parts of the route. I am sure, this helped me a lot to stay healthy and active. In a supermarket in Addis Ababa I also bought some chocolade bars that were also extremely useful when I was too hungry. I strongly recommend you to have some concentrates, chocolade, energy bars, or similar individual food reserves also for the days when you wouldn't get meals prepared. This may happen particularly on the day before departure for trekking and after the return from the mountains back to Dinsho. No one will care about your meals on these days. Although I had hired a cook, she didn't work while I was at Dinsho, and I even had to retain her salary for two days because of that. Fortunately, I had the pork preserves and chocolade bars, and could boil water on my Primus stove.

Overall, I lost about 5-6 kg of my body weight during this trip.

electric power

In the hotels in Addis Ababa and at Lake Langano where I was staying for one night on my way back from Bale Mountains the electricity was available without interruptions. Everywhere in the country European type of electric sockets with 220V current are common. People from UK, US and other parts of the world where other electric sockets and voltage are used need to bring adapters. I'd expect adapters to be available in shops in Addis Ababa but wouldn't rely on it. It is better to bring one or two from home.

Thanks to a Sunload MultECon solar charger there was light every evening in my tent. In the background on this picture a cave with camp fire is visible. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

There is absolutely no access to electricity while you are in the Bale Mountains. There are neither mains nor a car that you can charge the batteries of your devices from. Therefore, you have either to bring spare batteries for your camera, flashes and other equipment for the whole duration of your trip, or to charge them from a solar panel.

I had 8 LP-E6 batteries (for the main camera) and 5 BP-511 (for the second one). I use my cameras only for photography, never for video capturing, thus 8 batteries would be sufficient to power the EOS 5D Mark II for about two weeks, especially if I wouldn't use the Live View. With 2 or 3 batteries more I would have had enough electric power for my main camera for the whole time of trekking. However, powering many other devices, particularly those that need NiMh batteries, such as GPS, flashlights, photographic flashes, etc., is not that easy. I had over 30 AA rechargeable batteries and about a dozen of AAA, but they were still to few. Unlike lithium batteries, NiMh batteries get drained quite quickly. For example, I had to exchange the AAA batteries of my head lamp every two days. I didn't use flashes much during this trip, but if I did, it would most likely require at least 2 sets (i.e. 8) of AA batteries a day for each of my 2 flashes, i.e. 16 batteries. Certainly, it isn't possible to bring enough batteries for such use. The only possibility to power all necessary devices long enough is to recharge batteries when you are in the field.

Sunload 30Wp solar panel and MultiECon Charger M60 during charging process. Even if I didn't need fresh batteries immediately, I charged storage charger at every occasion. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

I had a 30Wp CIGS (Copper Indium Gallium diSelenide) solar panel and a MultiECon Charger M60 battery made by Sunload on this trip. This bundle is not cheap but is one of the best on the market. The foldable solar panel weighs about 1kg. Under African sun it needs as little as 3-4 hours to fully charge the storage battery. With a more powerful, though more expensive, 62Wp version, even less time would be necessary. This higher capacity may be of advantage in rain season or an area with more cloudy weather — when the exposure to sun is reduced and the charging process is slowed down. During dry season in the Ethiopian mountains most days were with bride sunshine, and the 30Wp version worked very well for me. To the MultiECon Charger M60 battery two such panels can be connected when quicker loading is needed. I am planning to get a 62Wp version in future and use it in expeditions to regions with bad weather even together with the 30Wp one. This would be also necessary with equipment that consumes more energy, for instance, a computer, that would more quickly drain the storage battery which would need to be recharged more often. Since my most used devices were 2 cameras (that had many spare batteries), a remote video control for a camera, 2 flashlights, GPS, and a satellite phone, I even used the 30Wp solar panel every couple of days. When the MultiECon charger was full, I could charge from it 2-3 camera batteries, 8 AA or AAA batteries, a lithium battery for a flashlight and the satellite phone in just one night.

The total weight of such solar energy equipment is almost 2kg. It is not really lightweight, but also not too heavy. It may not be suitable for a backpacker, but if your luggage is being carried by horses, 2kg less or more don't make much difference. The Sunload kit that I described above did an extremely good service for me during this trip. Therefore I am recommending it here. There are also similar products of other manufacturers that may be as good or better. You may take a look at solar panels and kits by GoalZero, Nature Power, me2solar, Brunton, and others. All such equipment that is suitable for use in harsh environment and will really be able to do the job of powering all your devices is quite pricy, particularly the foldable CIGS panels. To yield enough power from the sun you need a large surface. To be transported outdoors, it has to be foldable. Large foldable CIGS panels with 25Wp capacity and more cost starting from 300-400€, and there are no alternatives that would be cheaper and reliable at the same time.

hygiene

Certainly, there is no chance to take shower or bath while you are in Bale Mountains. I had a waterproof 10l sack called "pocket shower" that was supposed to be filled with water and hanged on a tree. Through a valve on its bottom the water will run down like in a shower. This all would have worked fine if there were a tree, but at high altitudes there weren't any or they were not high enough. The air was also too cold for showering. Therefore, I washed myself only before the trekking, in the middle of it — when we reached Harenna Forest — and upon return, in a hotel. In Harenna Forest days are warm and there are plenty of trees. So I could hang my shower sack filled with warm water.

Also washing cloths during the trekking is not really practicable. Of course, you can get water for it, but it will be cold and after washing you won't have time to let the cloths dry. Unfortunately, cloths get dirty very quickly due to much dust, but you have to live with it somehow and wait for an opportunity of washing. I recommend anyone going to Bale Mountains just to take enough socks, trousers, shirts and underwear for the whole time of trekking. Socks can be washed easier and dry more quickly, thus I washed them with cold water even high in the mountains. Nevertheless, a pair of socks for 2 or at least for 3 days should be a recommended quantity. (Note: All soap that you use for cloths and body washing has to be biodegradable.)

Brushing teeth, washing face and hands was also quite problematic. I was never observing that local people were doing it while they were in cold mountain climate. But I did: I washed the dirt and dust off my hands when I could, but had to reduce teeth brushing and face washing to one time a day. Of course, for teeth brushing and washing face and hands I used water that I treated with Katadyn purifying liquid.

communication

The mobile cellular phone network is quite extended in Ethiopia, and I was told that the tarif for inland calls was relatively low. I didn't use the mobile phone for two reasons. First, the battery of my Blackberry got broken for unknown reason in the first evening when I was charging it in my hotel room in Addis Ababa. I had no spare battery, thus my cellular phone remained dead till my return home. However, I even hadn't planed to use it on this trip. I knew that the cellular mobile communication isn't reliable in remote parts of the country. In Bale Mountains the mobile phones of my guide and horse assistants were working only in areas close to the main road and to big villages — Dinsho and Rira. For this trip I had rented a Thuraya satellite phone that was prepaid with 200 units. On it, I was writing 2-3 SMS every evening, and called at home every 5 days, and also every 5 days I received a phone call from home. This phone worked really well — even in the car, although it was a bit difficult to get it connected with a satellite when I was in Addis Ababa.

bottom line

costs and expenses

Compared to other countries of Eastern Africa prices in Ethiopia are generally lower. Unfortunately, everything is getting more expensive also there — not only due to global causes, such as increasing energy prices, but also due to economic growth in Ethiopia itself that results in higher life standards of the population and in growth of salaries. Also western tourists and expatriates are contributing to this process. I am afraid that the presence of international and foreign organisations with their large budgets has in this country similar impact on expectations of people as in some post-war Western African countries or in Rwanda: Growing demand for goods and services that these organisations create not only leads to extended offer but also result in attempts by locals to use the situation for making money through high prices. Rich tourists are still not as numerous in Ethiopia as in Kenya, Tanzania, or Uganda, but their number also grows constantly and contributes to increased demand for comfortable accommodation and transportation. Even being a western traveller who, according to popular belief, should have money, I had to refuse to stay in a hotel at Lake Langano which was looking like a midrange hotel in Europe but the rooms were priced from 150$. Even if I were willing to pay this amount, I could not get a room because the whole hotel was already completely booked — by western guests for whom the money obviously didn't matter. I knew that paradox already from Uganda — when a hotel accommodation costs three times the normal price just because money wasn't an issue for some visitors. Also in Ethiopia I had that bad feeling this time — i.e. that rich visitors of the country are making the life of budget travellers too expensive and at the same time help the already rich Ethiopians and foreign investors who control the infrastructure in making quick money while the majority of population that isn't involved in this business still remains poor. Unfortunately, a traveller, too, has to feel such one-sided “development” all over Africa. The less foreign “development” organisations or UN offices are active in a certain country, the nicer it is for a traveller. Ethiopia is not Uganda yet, but it is on the way to it.

During this my first visit to Ethiopia, the life cost of three weeks in this country could still be relatively low, if you didn't stay in Sheraton or Hilton, and were buying food in supermarkets or eating in budget restaurants. A budget hotel in city centre of Addis Ababa was priced between 20 and 35 € per night per double or twin room with breakfast. Single rooms, i.e. with only one bed, are rare. Therefore, even if you are alone, you have to take a room for two persons. If you will be insisting in having a “single” room, they will give you a double, i.e. one with a single large bed. Twin rooms have two beds but should cost the same. Cheaper hotels may still exist, but it would make sense to look for them if you are going to stay longer than one or two nights. I preferred a little more comfort and security that a hotel in the city centre has.

Meals in restaurants in Addis Ababa and towns at the road to Bale Mountains were also not very expensive, however, not that large as in Europe. Usually I paid around 6-7€ for a lunch or dinner including a drink — wine or beer. For the time of trekking I purchased food for about 50€. As I already mentioned, that amount would have been enough for me alone for at least a week or even ten days. At Dinsho and on the way in Bale Mountains, I paid all together another 100€ for the food of our whole group of 7 persons. However, this was the cheapest food that one could think of.

I was unpleasantly surprised by the price that I had to pay for honey in Harenna Forest. The guide requested 700 birr (around 33 euros) to buy a pot of honey when less then a week was remaining. I said that that honey was about as expensive as in European shops and didn't want to buy that much. The guide insisted — claiming that we had not enough food for breakfasts on the remaining days, and that there were no other alternatives. He also told that there were no smaller amounts of honey for sale — only that pot of 2.5 or 3 litres. Finally, I bought it. On the next days I ate not more than 200g of that honey; my trekking companions kept the rest. Certainly, I knew that I was being cheated, but decided not to refuse paying for that much honey because I wasn't seeing any possibility to get other food. Finally, I preferred to think about it as about some kind of duty or tax, or even aid for poor local people. All together, I paid for food on all 23 days of this trip to Ethiopia not more than 250€, or in other words — my expenses for food didn't exceed 11 euros per day.

A “briefcase” of a photographer travelling Ethiopia. A camera, lenses (including a super tele — of course), flashes and other small photo stuff were inside, along with a satellite phone and bales of banknotes — for this trip I needed four of them. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

As usually, transportation caused the largest expenses. The daily cost of hiring a car in Ethiopia depends on the number of days. Generally, it was as high as in other countries of East Africa that I had visited till then. You can negotiate a lower price — even less than 100$ — per day if you are going to use the car longer than a week. A typical price per day for shorter hire was between 120 and 170$. Since the driver had to overnight every time in Dinsho before he went back to Addis Ababa, I paid for two days more. All together for 5 days of the service of a driver with a car and for fuel I spent 750€.

Public transportation in Ethiopia is inexpensive. I used it only one time, however: My car hadn't arrived yet, and I had to take a bus from Dinsho to Rode and back to Dinsho for which I paid around 1.5€ one way.

The rest of expenses for this trip were national park permits, salaries of the support team and payments for horses. A large part of this amount were tips — around 250€. It looks like a big amount (and, in fact, it was — because I paid it alone), but that were only 3 euros per person per day — because 5 persons were the whole 19 days at my service. Considering that the regular daily salary of these people was only 5-7€, I found that at least so much gratuity was appropriate. Of course, I tried to pay according to the amount of work that the person had done for me. The guide who was working the most got my tent and 1500 birr. The rest of the money he decided to divide equally between the other 4 members of the team.

Overall, for this 24 days trip, including the flight, I spent about 2,500 €. If it were a mass tourism destination, such as Uganda, Zambia, or Tanzania, I am afraid, the same kind of travelling would have required probably twice as much money. (See my Field Notes from Uganda for comparison.)

peculiarities

As always, when I travel to a country and society with different traditions, social organisation, legislation, etc., I encounter and experience things that surprise me. In Ethiopia, too, there were things that appeared to me strange, or remarkably different than in countries where I lived or that I had visited before.

I would like to mention here some of such characteristic peculiarities that anyone travelling Ethiopia may notice.

Customs control at the airport: I had never seen a so chaotic and busy custom office before. When I arrived with my KLM flight from Amsterdam, two or three other flights landed. Therefore several hundreds of passengers were passing the passport control and the customs check. As in other airports of the world, there are green and red lines also in Addis Ababa international airport, however, there is no difference between them: the custom officers were attempting to check all baggage of all passengers arriving. There were only two or three baggage scanners, and not more than 3 officers were working at each of them. Others, maybe 3 or 5, were guarding the exit, not allowing the passengers to leave the area before their baggage was examined. I think you can imagine how long this procedure was taking! The custom officers weren't looking motivated to do their work thoroughly; on the other hand, passengers weren't patient enough to stand in a cue and many were walking around with their bagage carts attempting to come to a scanner before the others. First I tried to stand in the cue because I thought that there was one. Soon I realized that all this procedure was a chaos and that I could remain there for hours. Finally, I just went to an officer who was standing at the exit and told him that my baggage had been already checked, and he let me out.

Exchanging currency: Unlike other countries of East Africa, in Ethiopia dollars can't be used for payments in everyday life, i.e. you can't pay in dollars for any goods or services; you can't even give foreign currency as tip. Although there is a black market for it and foreign currency is in demand, it is difficult for an Ethiopian citizen to exchange it, therefore dollars, euros, etc., aren't normally accepted, and a foreigner has to exchange his currency against national currency, called “birr”. During my trip the exchange rate of euro to birr was between 1:22 and 1:24. Surprisingly, getting birrs for euros isn't that straightforward as you may expect in a country with market economy. I needed some birrs already on arrival in Addis Ababa — to pay for taxi and for dinner. As always in such cases, I had to exchange currency at a desk in the airport building. In all airports in the countries that I have visited before there are many such desks, both in the arrival and departure halls. I had expected it to be similar also in Bole International Airport of Addis Ababa but at arrival had to learn that it wasn't. There was only one exchange office just after baggage claim, i.e. after passport control and before customs. I didn't know it. So after I passed the customs control and didn't find any bank and foreign exchange offices in the arrivals hall, I had to go back — through customs to that only exchange desk. Fortunately, the customs officers allowed me to do this. Elsewhere in this country, you can exchange euros, dollars and some other currency in offices of banks that exist even in large villages, such as Dinsho. Don't forget to have your passort ready since it is required for the procedure. Small offices need to request a permission for exchanging a foreign currency every time they do it; the whole process may take half an hour or longer. Exchanging euros for birrs isn't a problem in the capital and big towns, but banks in villages may be exchanging only dollars. For instance, the only bank office in Dinsho is so.

Meals from menu often not available: I have never been to a restaurant during this trip where all meals listed in the menu were really possible to get. Of course, that weren't five-stars restaurants, but some of them were in midrange hotels or located in the centre of a big town or even of the capital, and thus were looking serious. Nevertheless, I had always to guess when I was ordering a meal and usually my guess was wrong; then I had to ask the waiter for a meal that was currently available.

No people with glasses: Ethiopians either have such good sight or just no tradition to wear glasses by someone who doesn't see well. I have no other idea why I have seen only one single person in a bank office wearing glasses. When I talked about it with my driver he told me that many people simply don't pay attention when they aren't seeing well to 100 percent and spare money not buying glasses. Well it can be an explanation but only for cases of minor or moderate shortsightedness. Among Europeans there are many people with strong myopia who wouldn't be able not only to do their daily activities at home and at work but even to safely come out of their house without their glasses or contact lenses. I also can't imagine a shortsighted person driving a car for long without a crash. Since Ethiopians do drive cars, but I never saw a driver who had glasses, I assume that shortsighted people rather wouldn't get a driving licence than get glasses.

safety, security, staying healthy

Compared to many other African countries, Ethiopia is a very safe place for travellers. I didn't observe even those hazards and annoyances that are being reported by so many tourists and that travel guide books usually warn of. I don't want to say that everything in such reports isn't true but I can't confirm it from my own experience. I never was offended or harassed even when I was walking alone in the streets of Addis Ababa. Nobody attempted to rob me or to steal something from my pockets or bags. Nothing of my equipment and belongings was stolen from hotels and the tent.

Okay, having read so many stories about pickpockets in Ethiopia, I left my cameras, phones and everything valuable, also money and credit cards, in the hotel. Going to the city, I took with me only a cut proof PackSafe wallet with some money and documents that was hanging on my neck. I had no hand bag and had nothing in the pockets. Although it wasn't evident to people on the streets that I have nothing of interest, nobody attempted to get from me something — even to ask me for some change. Overall there were not more beggars on the streets than in other countries of Africa that I had visited so far, and even than in Ukraine; and there were even less people who were looking dangerous. Street vendors were even much less pushy than, for instance, in Kenya — usually it was enough just to tell them once that you aren't interested in their offer. I read in many texts about Ethiopia that such people, particularly children, can be very aggressiv and insisting, but I never observed this myself.

All my baggage remained in a closet in my hotel room in Addis Ababa when I went to the city. I secured it with PackSafe nets, iron cords and locks. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

At the hotel reception, before checking in, I had to sign an obligation to watch for security of my belongings myself and not to blame the hotel if something gets stolen. It was pretty unusual condition because normally hotels have to do their best to provide security for their guests. In this hotel there were no safes in the rooms, nor lockers at the reception, nor any kind of lockable closets in the rooms. However, I was prepared for this: For such cases, I have a couple of PacSafe security meshes. They are made of lightweight but extremely hard twisted steel wire net that is very difficult to destroy. Of course, it is not 100% secure but one would need special tools to cut the wire, thus it protects against an occasional thief. Before living the room, I put both my bags each in one such mesh and locked them. I also locked my waterproof case where I had the most valuable equipment parts — cameras, lenses, satellite phone, etc. All this I put into a closet that was in the room, and tied together with a thicker metal cable, that I attached to an unmovable part of the armoire and secured with a padlock.

When I was travelling through the country, no one attempted to stop the car. I have seen police and military at the roads, but they weren't checking the cars — unlike in Ukraine, Russia, or even Turkey where a policeman can stop your car any time and without any obvious reason. However, the Ethiopian police might not do it for the same reason as the Ugandan — because they have noticed that either the driver or passengers are white. As a visitor of the country you won't have a chance to drive a car because an Ethiopian driving licence is required for that. Whether you will have any troubles with police and incidents on road, depends completely on your Ethiopian driver. Therefore, it is important to be careful when you are choosing the driver and the car.

The safest way to transport your photographic and other electronic equipment is to use a water and dust proof polycarbonate case, such as Pelican, or similar. A big disadvantage of such cases is that they are quite heavy. A big Peli case, when it is empty, can weigh 20kg, almost as much as the most airlines allow in checked luggage. Also most airlines allow only 32kg of maximum weight per piece of luggage even if you would pay for overweight. Therefore, large polycarbonate cases can't be used at all on such trips, and bulky equipment items, such as tripods, have to be transported in soft-shell luggage instead. On this trip I had only one hard-shell waterproof case that I took into airplane as hand luggage. It served me very well in Bale Mountains protecting my lenses and some other equipment from dust and physical damage. Since it couldn't accommodate all potentially fragile equipment items, I had always to worry about those items that had to travel in bags. They certainly weren't safe there. Next time when I'll go to Ethiopia, I will take two such cases — i.e. one more that this time, to be able to put all fragile items in hard shell cases.

In dry season, almost everywhere in Bale Mountains the soil looks like this: There was no vegetation — only remains of dry grass and dry dung of goats, sheep, horses, cows. This produces enormous quantities of dust, that is being carried by wind and that covers you and your belongings, not only from outside but also inside. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

A horrible place: Heather zone (ericaceous belt) at altitudes below 3500 m a.s.l. Maybe it is better in a more wet season, but in February and early March it is an extremely dusty and almost lifeless area of dense heather bush that is very difficult to pass. You can walk only in spaces between walls of heather trees that have deep rills made by erosion and hooves of cattle. You can puncture your shoes and or even break a leg at any time, so you have to watch your steps for many hours. Doing it for many hours is very boring. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

Since there is always a danger that you break your camera if you fall or drop it occasionally, I recommend to have at least two camera bodies. Also getting an equipment insurance should be a good idea, particularly if you have a lot of expensive gear.

You should also be careful of dust. Bale Mountains was the most dusty place I ever visited; even in Kenyan savannah there wasn't as much dust as in Ethiopian highlands. I have no advice for such situations: It isn't possible to provide complete protection against dust because there is just too much of it. If you would pay attention to dust and try to prevent its intrusion into your equipment, it will spoil all your trip. I decided to relax and to take only reasonable amount of care. In the night, when the air was more clear, I cleaned lenses and cameras as much as possible.

In terms of health hazards, Ethiopia is also relatively safe. Malaria, a desease that Africa travellers are the most afraid of, is virtually absent in this country whose territory lies either at high altitudes or in areas with dry climate. Anyway, there is no danger of malaria in those regions of Ethiopia that I have visited during this trip. Therefore, I didn't take any prophylaxis against this desease. The risk of getting infected by parasitic worms doesn't exist at high altitudes, too. Even in Harenna Forest I used water from the local river for shower without any treatment, and didn't get an infection.

However, there are two deseases that a traveller has to be warned of: meningitis and typhoid fever. Outbreaks of meningitis happen now and then in tropical Africa including Ethiopia but they are localised to certain small areas that are quickly put under quarantine. Chances “to be at wrong time in wrong place” are not very big, particularly when you are an outdoor traveller who has little contact with local population.

There is a much greater risk to get a typhoid infection. There are two ways to prevent it. One is to get immunised by your family doctor before the trip. The other possibility that any doctor would recommend is just to be careful — first of all to avoid drinking and swimming in water that may be contaminated with human feces and urin. Since typhoid fever is rarely a life threatening desease nowadays and immunisation isn't reliable, it is enough just to be cautious.

As almost everywhere for an outdoor photographer, also in the Ethiopian mountains the risk of an accident and injury is quite high. This was the main reason for me to have a satellite phone on this trip because I was travelling alone — only in company of Ethiopian helpers. Certainly, it is advisable for everyone trekking or hiking in such countries to have as good insurance as possible that would also provide evacuation in case of emergency. Also it is good to have a first-aid-kit and important medicaments — analgesics, antiseptics, etc. Even if you can't yourself provide a medical aid, it is better to have everything necessary because there can be someone who would be able to do it.

In my opinion, it is the high altitude that causes the most serious health problems. I had read in books about mountaineering that different people have different reaction to high altitude and not all suffer altitude sickness. Though I had been at altitudes greater than 2500 m above sea level before this trip, I never got sick because of that, hence I didn't know that for me altitude sickness may be a serious issue a all. I had to learn it already in the first night of my stay at Dinsho: I couldn't go to sleep because of dyspnea. The next days it got worse: I was getting breathless already after very short physical activity, often had bleeding from nose that finally got clogged with blood thus breathing got even more difficult, had very little sleep, I could hear my heart beating very quickly somewhere in my head... As if it wasn't bad enough — I had to walk every day at 15-20km on dusty plains, climbing hills at over 3500 m a.s.l., carrying heavy load... and breathing dust. After a week I was getting really desperate because I wasn't feeling better. Suddenly, 10 days after beginning of the trekking my illness stopped as suddenly as it had started although I was at altitude over 3800 m above sea level. All symptoms were gone soon, and I was feeling normal for the rest of the trip.

Having had such troubles, I would advice anyone going for a long trip in Bale Mountains or any other area in Ethiopia at altitudes over 3000 m above sea level to take the risk of altitude sickness serious. If you aren't in good physical shape and not young, I think it should be a good idea to get your health condition checked by a physician.

My face and hands got burnt by the sun already on the first day and I had to protect them with scarf and gloves that I was wearing all the time on sunny days during this trip. Certainly, I had sunglasses and a hat on in most hours of the day. (Click on picture to enlarge.)

The last but not least health relevant issue that I would like to mention here is UV radiation and skin burns that is causes. Everyone has heard about potential danger of skin cancer caused by it. I heard it, too, and certainly would have tried to avoid sun burns — if I could, or better to say — if I had time for it. I didn't even notice how I happened. I was very tired after long walk on the first day and because of my altitude sickness; I laid myself down on top of a hill to rest for about 20 minutes — with my face up. In the evening I felt that my face and hands were hot and burning. The next day they were all red and swollen. This continued for several days: I was getting vesicles on the nose that were bursting, and liquid was leaking from them. The wounds were healing quickly but the signs of them remained till the end of the trip. Even when my driver came for me to Dinsho, he told me that I was looking as a completely different person than the man whom he had brought with his car there weeks earlier to this place. For my next trip to Ethiopian highlands I will take sunscreen and will be more careful with the sun. I will also from the beginning of the trip protect my hands and face with cloths as much as possible.

photographic experience

In terms of photography, my experience during this trip was quite mixed. On one hand, I had opportunities to watch and to photograph some endemic fauna, and in this sense the trip was quite a success. On the other, the weather and the season weren't optimal. Of course, there is no such thing as a location or time not suitable at all for photography, and it should be possible to get good photographs in all situations, but some places and occasions are better than the other. Though I brought many good images from this trip, I know that it could be much more if the season hadn't been so dry and the weather not so sunny.

wildlife photography

All three regions that I have visited in Ethiopia this time — Bale Mountains, Harenna Forest, Rift Valley — have good locations for wildlife photography. As I already mentioned, I had planed this trip with concrete subjects in mind — reptiles and amphibians, Ethiopian Wolf, Bale Mountains Vervet, and some other mammals. Since there were no opportunities for serious herping, I concentrated my efforts on photography of other wildlife. All equipment that I brought for herp photography — close-focus and macro lenses, macro flash, flash brackets, snake catching equipment, etc. — wasn't useful at the locations that I visited and with the subjects that I was able to find. Also the flora was very scarse due to this dry season — no flowers, little green foliage, everything was looking yellow and dusty...

Invertebrates & Co.: During rainy season there may be good opportunities for macro photography in Harenna Forest and at Dinsho village but not at high altitudes in Bale Mountains. Hence, if you are going to spend most of your time on Sanetti Plateau and in the valleys at 3500-4000 m above sea level, you may consider to leave your macro equipment at home. Anyway I'll do it if I would go to this area again.

Birds: Bird photographers will find great opportunities in all areas that I visited. I have seen very many bird species even in this dry season and photographed some of them though birds weren't the main subject of my interest this time. The bird fauna was particularly rich at Rift Valley lakes, in Harenna Forest and at lower altitudes of Bale Mountains. At higher altitudes raptors are more frequent but less passerine birds.

Just as everywhere else, for bird photography in Ethiopia a long telephoto lens — preferably with focal distance of 500 mm and more — is necessary. And, as usually with birds, you will need to use even that lens quite often with a teleconverter. Carrying such a big and heavy lens and a suitable tripod for many hours in the mountains, particularly if you are altitude sick, isn't really practicable. If you put it on a horse, you won't be able to use it on the way. Even the latest 500 mm and 600 mm lenses which are more lightweight than predecessors are still too heavy and too bulky for use during trekking in the mountains, when you are carrying a lot of other heavy stuff such as other photo gear, drinking water, food, etc. Therefore, a specialist in bird photography may prefer to spend more time at the locations that can be reached by car. Dinsho, Sanetti Plateau, Harenna Forest and Rift Valley lakes certainly are so. The Abidjata-Shalla National Park is a particularly good place for photography of savanna birds, such as ostriches, hornbills, and many species of passerines. Since both lakes have solt water, a swarm of flamingos lives on them along with pelicans and some other shore bird species. Unlike on Tanzanian and Kenyan solt lakes, the birds on lakes Shalla and Abidjata are very shy and fly or run away if a person tries to approach them closer than 150-200 m. Of course, this distance is much too large for such small subjects even if you have a super telephoto lens.