field notes

ukraine, 2010

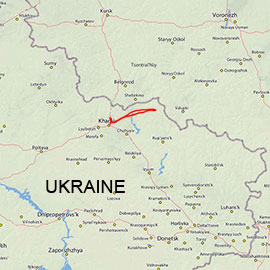

In early spring 2010 I could spend two weeks at my home in Kharkiv. I used this opportunity for photographic excursions. I was hoping to find some amphibians and even Nikolsky adders, but the winter had been very cold, and there was still plenty of snow in forests and ice on ponds and rivers. Nevertheless, I had three quite successful excursions. One of them was particularly exciting because I had a chance to photograph bobaks. Their range reaches in the west the Eastern-Ukrainian steppe. Therefore they are, after the Alpine Marmot, the second European marmot species. I could find these animals and make some good photos thanks to support by my friend who works as zoologist in local zoo.

My visit to Kharkiv had to be during Easter holidays. Therefore I wasn't free to choose the season. Though it was in early April, I had been expecting that the weather would be warm enough at least for some early-breeding amphibians.

landscapes and amphibian habitats in early spring

Unfortunately, my expectations to find breeding moor frogs and even basking adders didn't prove. The temperatures were not high enough. There was still ice, on rivers and on lakes, and some snow was in forest. Nevertheless, I made two excursions in the forests near Kharkiv looking for wildlife and landscapes. The forest walks were not only pleasant but photographically quite rewarding. Both excursions were actually to the same area, but to its two different ends. The images that I captured during them are now presented in the theme Alder Gorge.

First, I went to the place that I personally new very well because I had been there many times before. It is a chain of seven lakes (in fact, large artificially created ponds) situated in a gorge whose slopes are covered with dense wild woods. Locals call this place "Olkhovaya Balka" ("Alder Gorge") though I have never seen this name on any map. I've been told that at least the western part of this area is protected now as a natural reserve. But I went first to the gorge from the east because it was closer to the place where I live in Kharkiv.

It is quite easy to get there. The gorge begins in the west — several kilometers from the village Russkaya Lozovaya — and ends in the east about 2 km from the village Borschevaya. I usually start my walks in the gorge from Borschevaya lies at the banks of Kharkiv River, near Liptsi — a small town some 20-30 km from the city. You can go there by taxi or by bus. However, municipal line buses don't go anymore, and you have to take a minibus operated by a private company. It costs not much: In 2010, it was about 0.50€, or about 0.70$. The drive to Borschevaya from the bus stop near the underground station "Geroyev Truda" takes about 20 minutes.

If you want to walk the complete distance between the villages through the gorge, you should plan with at least half a day. It should be a whole day, if you will be photographing. Otherwise, it is possible to cover only a part of the area, i.e. you'll have to return where you started — to Borschevaya or Russkaya Lozovaya. Anyway, in the season between October and April, the days are too short, and you won't have enough time for the whole way. In late March, when I visited Olkhovaya Balka, I had time to walk only around the three lakes close to Borschevaya, i.e. in about one third of the whole forest.

The forest in Olkhovaya Balka looks intact and may be at least partially even a primary forest. It was not planted as a whole but its parts were logged now and then in the past, so that younger trees grew. In the western part, today, illegal loggings occur. On the northern slopes near the lakes, alder is the dominating tree species that gave the name to the place. On the southern slopes, there are quite many oaks but few trees look older than 50 years.

I hadn't been to Olkhovaya Balka since 1997 and didn't know what happened there since then. When I returned 2010, almost 13 years later, I was very glad to see that the turbulent years of wild market society in Ukraine hadn't had much impact on the nature in this place. The lakes and the forest appeared to me even more wild and abandoned than in times of Soviet Union. There were absolutely no people around, and no signs of human activity at least since the autumn. Having seen in Europe only the cultivated nature of Germany and Poland, I was absolutely amazed to find such wildness on this overpopulated and overexploited continent.

Olkhovaya Balka is a quite cold and moist place. In the time when I came there, the lakes were still covered by ice although the most rivers in the region were already free of it. Under the trees on the northern slope of the gorge there was still much snow, while almost everywhere else in that region, ephemeral plants were blooming, and snow was already absent. I saw a buzzard couple and some chaffinches, but overall very little wildlife. Since the sun was going down, I concentrated myself on landscapes. The mood of that sleepy forest and cold lakes was fantastic! I had no tripod and my only wide-angle lens was a 15 mm fisheye that I took with me because I was going to photograph amphibians — not landscapes. However, I like the landscape and flora shots that I did with a fisheye lens during that walk very much. Maybe, the results were even better if I had a tripod and a landscape lens, but maybe not. Other lenses in my bag were a 300/2.8 telephoto and a 2.8/150 macro, but I couldn't use them because there were virtually no suitable subjects and the light conditions were quite bad. With the macro lens, I only made some shots of lichens that were very diverse and colourful.

In Western and Central Europe you won't find this beauty: A blue carpet of Siberian squills.

A couple of days later, I went to a place that is adjacent to the western end of Olkhovaya Balka. The day was sunny and much warmer. The floor in many parts of the forest was blue because of countless blooming Siberian squills. I went to that excursion with a friend who knew places where he collected Nikolsky adders (Vipera berus nikolskii) many years before. Unfortunately, we couldn't find any snakes that time. Although the forest had changed in the past years, the changes were not looking critical for the ecology of adders. I suppose that either it hadn't been long enough warm for the snakes to be active or we didn't find the place. The way through the forest to the place where we were expecting to find snakes took us quite long, and I didn't photograph other wildlife because we were in a hurry to reach breeding places of amphibians before sunset.

In the late afternoon, we reached a lake that was partially frozen but, to our surprise, in the woods near it we found many common toads. The toads were very active: males were in search for females to clamp on them for mating. Some males were already riding on females towards water. I had been thinking that moor frogs were breeding before other anurans in this region, and was surprised that common toads were that. Although we didn't find any moor frogs, I was glad to photograph toads with breeding behaviour. I made many shots with a 15 mm fisheye and a 150 mm macro lens. Since the toads were active, they were permanently trying to escape when I was approaching them with a camera. Therefore, I had to handle them a little: to hold in one place or to put in a better position.

The biggest problem for a naturalist in Ukraine appears to be transportation. A car is still a luxury that most people can't afford. If you don't have your own car in this country, you'll have to go to nature locations by public transportation. In 2010, car hire was still uncommon or even absent, and it may be quite dangerous to drive a car in a country where people regularly don't adhere to rules, and police officers are watching for own profit rather than for law and order. I have been told that car hire offices exist in Kiev and some other big cities but didn't see any myself and therefore don' know their conditions. Since I came to Ukraine without my own car and didn't have an opportunity to rent one while I was in Kharkiv, I had to go by public buses and minibuses. This was very time consuming. I arrived at most places very late because of that, and, to catch the last bus going to the city, had to finish photographing and to leave the location always very early.

photographing bobaks

Bobaks, or Steppe Marmots (Marmota bobak) have a huge distribution area ranging from the western Altai Mountains to the east of Ukraine and the south-western provinces of Russia. Kharkiv region in Ukraine is one of few places in Europe where this species can be found.

This steppe habitat has recovered from pasture. Now, it is similar to its original state — as it was centuries ago. It is a place with great variety of flora and fauna, but you won't find any bobaks here. They don't like areas with grass so high.

Here you see a typical habitat of bobaks. When farmers have burnt the steppe, and green grass starts growing, and cows have come, bobaks will settle on this place soon.

In the European part of their distribution range, bobaks became rare in the last century due to habitat destruction caused by extensive agricultural use of the steppe. Therefore in Europe it is a potentially endangered mammal species. Luckily, the growth of agriculture in Ukraine and Russia in the past was not as powerful as in other parts of Europe, and now it has even slowed down. In Ukraine, the agricultural production, even decreased significantly after 1991, and the steppe is slowly returning on abandoned agricultural land. Ironically, this process is not always for the benefit of bobaks. These animals seem to live only in areas with low grass and won't remain long in such places where the grass grows high in the summer. If they aren't hunted or otherwise disturbed by people or dogs, bobaks can successfully co-exist with cattle. Grazing cows or horses not only aren't disturbing them but they are an important component of bobaks' habitat. The decline of cattle breeding in Ukraine indirectly causes the decline of bobak population when the abandoned pasture land gets overgrown with high and dense grass. Researchers argue that the reason is in behavioural ecology of the marmots who always need a free view to be able to escape or to avoid predators.

My friend from Kharkiv Zoo — Dmitriy Strelkov — and I went to look for bobaks to a quite remote area — about 115 km away from the city. For Ukrainian conditions it is a quite large distance. Without a car, it is impossible to get there early. I had an idea to go by taxi. In Ukraine, a taxi outside a city costs a double price because they charge for the way back even if they return without you. Even the double price for a taxi from Kharkiv to Velykyi Burluk — a town where we were going — was less than 30€. Of course, the taxi company and the driver were quite surprised by that order because they apparently never before had a client wishing to be taken so far from the city. We decided not to start when it was dark, so the taxi picked us up at 6.30 a.m. We leaved the city at 7.00 a.m. and arrived at the bus station in Velykyi Burluk at about 9.00 a.m. First, we weren't sure where to look for bobaks. We knew that they build colonies on slopes of hills in the area around the town. Before the trip, Dmitriy had attempted many times to contact an expert in this species at Kharkiv University for consultation but didn't succeed. We decided to go to Verlykyi Burluk and call the scientist from there to ask him where to go. This time he was on phone. He told us that we had to go either to south-east — to village Katerynivka — or to south-west — towards Gnylytsa River. Both places were quite far from the town. Unfortunately we had already released the taxi and needed to take a bus to go there.

Velykyi Burluk has a quite serious-looking bus station, with a large building and even a ticket office. We didn't see any large buses, however, but only minibuses — as everywhere in Ukraine today. I asked at the ticket office if there were a connection to Katerynivka but received the answer that the only minibus on this day already had left. But the next minibus to the other place was going to depart soon, and we took it.

The place we were going to was about 16 km away from Velykyi Burluk. The road to it was the same as to Kharkiv, via Pechenegy and Chuguyiv, i.e. the one we had to take to return to the city. Before our departure from Velykyi Burluk, I asked at the lady at the ticket desk about the last opportunity to leave for Kharkiv. The answer was: 4 p.m. I also asked her if we can get on that bus at the place where we were going, i.e. not in Velykyi Burluk. She told that, though we had bought the return tickets to Kharkiv, we had to come back to Velykyi Burluk first, to ensure that the bus will take us. She also told that, to be in the town till 4 p.m., we had to go back already at about 3 p.m. — by the minibus going from Kharkiv to Velykyi Burluk, i.e. the very same that we had tickets for and that will later bring us on the same road (!) back to Kharkiv. In Ukraine, things trivial elsewhere in Europe are often made very complicated and may appear quite stupid to a foreigner. If you are used to European or American kind of service, you should be prepared that Ukrainians have a completely different concept of it: Persons and companies in this country who are offering a service of any kind and in any area — transportation, communication, gastronomy, etc. — typically care not for comfort, benefit or satisfaction of their clients but for maximum profit.

My friend — zoologist Dmitriy Strelkov — is looking for bobaks.

After we got off the bus, we went looking for bobaks in a direction that the bobak expert had told us on phone. In about a kilometer, we asked a man who was working on his tractor about the animals. As we had expected, local people new bobaks very well, and the man told us that, if we go a bit further, we would see them soon. After we passed some abandoned cowsheds, we saw a beautiful grass landscape. It was about 10 a.m. when we finally had reached the place of our interest.

Soon, I heard a whistle that was unmistakably a call of a bobak. When these animals are alert they give a short single whistle. Usually they see you earlier than you notice them, but the whistle that an individual uses to alarm the others would always reveal its presence. Thus, listening for whistles is the best way to find bobaks. A binocular can also be very helpful. The terrain in this area is hilly, and you can look very far from one point. With a binocular, we were inspecting the slopes and sometimes could find bobaks before they got alerted by our presence.

A burrow of a bobak looks like this.

Bobaks are always grazing near entrances of their burrows. When I was at their colony, it was one of the first days they had left their burrows after hibernation in winter. Many animals appeared thin and exhausted. Though the weather wasn't stable, they were trying to stay as long as possible on the surface and to feed. When I tried to approach them for a photo, they ran into the next entrance of the burrow but usually didn't stay long inside. I used this behaviour for my benefit: To approach an animal close enough for a full-frame shot, I walked to the burrow entrance while the bobak was inside and waited till it looked out. If I wasn't moving, the animal, finally came out. It escaped in the hole again when I made just a little movement. But next time it came out much sooner. After I played this game with one animal for about an hour, I managed to come so close to it that I could use my 300 mm lens without teleconverter, and the animal filled the frame, i.e. I was in about 4 m from the bobak. I could come even closer but didn't need it.

To photograph bobaks, I used a 300 mm lens (EF 300 mm F/2.8 IS L USM) on EOS 5D Mark II. I also had a monopod that I was using as a support for my lens and camera when I was waiting for a bobak to come out the burrow. The scenery at that place was fantastic, and I made many landscape photos (with EF 17-40 mm f/4 that I had with me too). In Europe, you find a better steppe area maybe only at Volga River in Russia and in southern Ukraine. The place where I was photographing bobaks in Kharkiv region must be more beautiful in the summer — when steppe plants are blooming — or in the autumn — when the grass is high and the steppe looks like a sea. I am certainly going to come again to this place in June or September.

Our way back to the city was the most adventurous part of this trip. As I already mentioned, to catch the minibus going from Velykyi Burluk to Kharkiv, it was necessary to go back to Velykyi Burluk first, although the place where we were was on the way of that minibus. We had been told that, to get back to the town, we could stop the bus going from Kharkiv to Velykyi Burluk that was passing at our location at around 3 p.m. To be able to catch the bus, we left the bobak colony already before 2 p.m., i.e. we had spent there less than 4 hours. Well, even so, I managed to make some good shots of bobaks and steppe landscapes, but, compared to the time we needed for the way to the location, the time we spent there was too short.

After we reached the road, we decided not just to stand and to wait for the bus that would take us to Velykyi Burluk but to walk. The minibuses in Ukraine don't have mandatory stops nor a timetable: They leave when they are full and stop on passenger's request. As we had to learn later, it was a right decision — to walk.

We were walking already for half an hour, but no bus came. There was not much traffic on that road at all: In one hour of walk, we saw not more than 10 vehicles. One minibus and one line bus didn't stop at us although we were making signs. No other car stopped. We realized that we won't be in the town before the departure of the bus to Kharkiv, if we wouldn't hurry, and we were almost running. In two hours, we managed to walk about 14 km. (Of course, I was carrying heavy equipment on my back.) Finally we reached the town, and when about two kilometers were remaining till the bus station, we saw that we were late — that the time was over. We decided just to stand at the road and to wait — hoping that the minibus that has left the station would stop and take us. And a miracle did happen: The driver saw us and stopped! We got on it — tired but happy. Soon the bus passed the site where I was photographing bobaks, and in another two hours we were in the city. But the question remained: Did our walk make any sense?

final remarks

If you travel in rural areas in this country, at least basic knowledge of Russian or Ukrainian is a must. No one will be able to communicate in any other language nor understand what you are saying unless you were lucky to have encountered a university student who came to visit relatives in his/her home village. In cities some people (especially, young) may speak a little English but you shouldn't rely on this possibility. In Ukraine, officials, such as police officers, also speak only Russian (or Ukrainian). So, if you happen to have got in any kind of trouble and don't speak local language, your trouble may become much more serious!

I wouldn't advise a foreigner to go alone. People there aren't dangerous but may appear not nice to a foreigner. You will feel more comfortable if you would have company — especially if it is someone with local knowledge.

What I would do differently next time:

- In spring, I would go to forests and lakes in Kharkiv region about two weeks later than I did this time — maybe in mid April. However, it would depend largely on weather and on temperatures in winter. If the winter was cold and with much snow, as that year, late March - early April is definitely too early for amphibians.

- I was missing a tripod. I didn't take my Quadropod because my checked luggage was already too heavy. But I was missing it every minute when I was photographing landscapes.

- If I would go to photograph bobaks again, I would either overnight in Velykyi Burluk or at least arrange a pick-up by car in the evening instead of leaving the bobak colony at 2 p.m., as I had to do in order to catch the last car to the city.